This account was written about 20 years ago and ‘vanity published’ as a pamphlet. It was intended to be a readable story suitable both for those interested in social conditions and in local history. Unfortunately an attempt to get the National Mining Museum at Caphouse Colliery interested in publication and distribution failed. It has now been out of print and unavailable for years. The author is in the process of rewriting it to include new material taking the history of local coal mining up to the 1920s. Notes towards this can be found at:

COLLIERS AND HURRIERS

WORKING CONDITIONS IN COLLIERIES AROUND HUDDERSFIELD

c.1800-1870.

Part I.

Introduction

On 28 March 1574, Thomas Boothe of Newsome Wood buried his wife Katherine and married again to Alice Crosland on 25 July. Their nuptial happiness was short lived. The following March, Thomas, “by sodeyne mischaunce was slain in a coal pytte the roof falling upon him and was buried.” Alice died in childbirth a few months later at least partly due, we may suspect, to her bereavement.

This episode illustrates the nature of much of the evidence which follows. It is only when some tragedy occurs or when some grievance needs to be redressed that the underground existence of the miner comes to public attention. But even then it is very difficult for those who have not worked in a mine to imagine the conditions, even if vividly depicted. From numerous scattered references and a couple of more detailed accounts we are however, able to build up a fairly comprehensive picture of work in local collieries in the period before the emergence of modern legislation and technology ended mining practices which, in some ways, had changed little since the Middle Ages.

This is a very localised study, covering only about 100 square miles on the periphery of the Yorkshire coal field but, apart from being of intrinsic local interest, it is hoped that this will complement broader studies and serve as a reminder that the mining industry of the industrial revolution was typified by the small colliery in a rural setting, rather than by large scale operations with which later deep mining has become associated.(1)

The Development of Local Coal Mining.

Although this account is not primarily concerned with the techniques and economics of mining, a brief outline of its development is necessary. The pit where Tom Boothe met his death must have been that described ten years later as, “a cole mine of small value digged and wrought by John Lockwood or by others…” as it was the only one then in the Manor of Almondbury. (2) Colliers are referred to in the Almondbury parish registers in 1605 and 1651 again, in both cases, being Newsome men. (3) As early as 1515 coal was being dug at Flockton in the adjacent Manor of Wakefield (4) but in the 16th century wood and charcoal probably remained the main domestic and industrial fuel.

In 1636 John Kaye was digging coal at Rowley for use at Woodsome Hall (5) and by 1698 there was a colliery at Honley and several in the Emley-Flockton area. (6) The 18th century saw a rapid expansion. Coal beds are referred to in a lease of lands at Honley in 1754 and in 1779 a shaft at Oxlee at Hepworth was described as “lately put down and Mr Firth has begun to get the upper bed for which he has excellent sale.” (7) This may be the same as Law Colliery leased in 1784. (8) Coal pits at Fulstone are referred to in the Land Tax Returns for 1792 and by the close of the century all the major landowners had collieries on their estates. Ramsden leased one to Bradley & Co. at Huddersfield, R.H.Beaumont leased a number on his lands at Kirkheaton, Milnes & Jaggar worked one of Sir John Kaye’s land at Kirkburton in 1787 and Lord Dartmouth had three at Honley and Brockholes, one at Flockton and another at Breistwhistle. (9)

The 1805 Dartmouth Estate Terrier reveals that the right to exploit so many acres of coal was leased by the landlord and the running of the colliery left – sometimes with uneconomic results – to the lessee. Of Westwood colliery at Honley it was reported, for instance,

“…the mine which has been worked in an improper way for many years is nothing like so productive as Jos Haigh’s although the collieries are very near each other. The present tenant Widow Jaggar has been imposed on by the colliers & the works very ill-managed so that the Mine cannot at times be worked on account of water in it. she is however desirous of continuing Tenant although I fear it will never answer to her. ”

Although it was in the landlord’s interest to ensure efficient exploitation and therefore maximum rents, Dartmouth’s intervention seems to have been limited to fixing a fair sale price for coal since the local customers had suffered from short measure and overpricing. However, another large landowner, Sir John Lister Kaye, worked his own collieries near Flockton under an agent.(10)

The growth of the coal industry was integral to all the other economic developments which together made the industrial revolution. It was not a case of simple, mechanical cause and effect, but of complex action and reaction of each industry or economic change upon many others. Some direct relationships are nevertheless evident. The development of canals undoubtedly facilitated the transportation of coal and locally we have clear illustration of this. In 1806 coal was taken directly from William Bradley’s drift mine by means of a railroad, “to the South End of the Town of Huddersfield and to a Wharf adjoining the Canal…” This example also reveals how, in turn, other industries were stimulated since on the Almondbury side of the property, a copperas works was built to be supplied from the colliery.(11)

A report of an accident at Horsforth refers to a colliery which was reopened around 1800 after sixty years in order to supply steam engines at scribbling Mills. (12) This must have been a factor in colliery development in the Huddersfield area also where the number and size of steam engines grew steadily from the 1790’s. Sometimes there was a direct link between mining and textile capital. At Linfit Lane, Kirkburton, Hey & Carter had a tram road running direct from their colliery to the mill. (13) John Hinchliff, a Jackson Bridge scribbling miller, owned a colliery which employed 40 men and 35 boys in 1851 when another millowner, William Shaw of Holmfirth employed 12 men and 13 hurriers in his pit and 9 men and 14 children in the mill. (14) A Kirkburton manufacturer, Wright Rhodes, sank a new shaft in Kirkburton in 1867 and the Norton Brothers, extensive fancy manufacturers who were involved in mining in Clayton West at least prior to 1856 opened collieries at Clayton Common and Duke Wood in about 1862/63. (15)

Colliery sizes varied widely from the small ones in the Pennine valleys, such as that of Uriah Tinker at Meltham employing 10 men and 10 boys in 1851, to the 137 men, 114 boys and 14 girls who worked for Edward Beecher, agent for Sir J.L. Kaye in the Flockton area. (16) In at least three cases small mine owners were also publicans and yet others were farmers. (17)

The geographical extent of local coal mining is evident from the first six inch series of Ordnance Survey maps surveyed around 1850, although these do not make the size of a colliery, or whether it was still working, apparent. According to Mrs Jaggar’s History of Honley, Haigh’s Hall Ing Collieries were closed as a result of the opening of the railway in 1851 which allowed coal from Barnsley pits to be imported into the Huddersfield area.(18) However, in 1856, during the Commons Inquiry into the Kirkburton to Barnsley railway bill, John Sheard, a Lepton mine owner and surveyor said that the previous year only 29,000 tons came from Barnsley and it offered no competition in the Huddersfield area. In the Clayton West area where the proposed line was to run, only 30hp of steam power was in use and it was supplied by local coal. A total of 346,173 tons was consumed around Huddersfield which used some from the Batley-Dewsbury area and much of Sheard’s own coal was in demand for smelting.

The reasons for the contraction of local mining can not be ascribed simply to the advent of the railways, which in some cases may even have had a beneficial effect. Whiteley’s Thurstonland colliery had a siding at Brockholes in the 1860’s for instance.(20) The closure of Hall Ing colliery may also have been due to the exhaustion of reserves as was the case with Uriah Tinker’s Lower Holme House colliery near New Mill where the plant was sold off in 1862 (21).

Coal production reached a peak in 1867 with 384,700 and 112,500 tons being produced by Huddersfield (not including Flockton) and Holmfirth collieries respectively, declining in 1868 to 300,500 and 87,470 tons. The output of about 36 collieries in the former area and 13 in the latter fell the following year to 111,295 and 36,537 tons and had slumped by 1872 to only74,757 and 25,732 tons. (22).

The period of this essay therefore covers the heyday of mining in the area. But, whatever the changing patterns of coal production between 1800 and 1870, working conditions changed little for those underground. The depth and thickness of local seams will be referred to below in the context of specific collieries. In general they varied from 18 inches or under (one at Greasy Slack colliery at Meltham Mills in 1805 was only 16 inches) in the Holme Valley to 36 inches plus in the Flockton, Breistwhistle and Cumberworth areas. (23)

The usual method of colliery working in Yorkshire by this time was by benks (see Diag.1), an intermediate practice between the wasteful pillar and stall method which left a lot of coal intact to support the roof, and the longwall method used today where most of the seam is extracted. (24) Although gunpowder was used in collieries, at least by 1820, there are few local references to it. The coal was worked at the face of the benk by the collier using a hammer, wedges and a pick and lifted or shovelled into a corve to be transported to the pit bottom by the hurrier.

Child and Female Labour

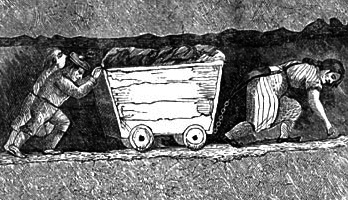

A hurrier and two thrusters heaving a corf full of coal as depicted in the 1853 book The White Slaves of England by J Cobden.

Hurriers were as vital to the operation of a colliery as were the colliers. They were invariably children or women and as in textiles and many other trades in the industrial revolution, coal mining could not have developed without the exploitation of this source of labour power. It was the hurrier’s job to push or pull the corves full of coal to the pit bottom. These were originally dragged like sleds but, by the 1850s at least, rails were coming into general use. In 1864, plant sold at Tom Gelder’s pit at Clayton West included 380 rails and 8 corves of two hundredweight and one quarter capacity (25). At other pits the size of corves was probably different – in the Halifax area they varied from two to five hundredweight. Often the gates (underground roadways) in which the hurrier worked were little higher than the seams, being only two feet high at Briggs colliery at Flockton in 1842. (26)

As early as 1699 we hear of the burial of Isaac Crowder, “a poor boy being slaine in a coale pitt at Flockton”, the term “poor boy” perhaps indicative of a parish apprentice (27). Other hurriers worked under the supervision of colliers who were their fathers or other relative. John Dixon, secretary of the West Yorkshire Miners’ Association in 1865, started work in a pit at Breistfield in 1835 at the age of 7, hurrying for his father.(28) But even a parent’s presence could not always alleviate the dangers or horrors of pit work. After the loss of one son in a roof fall two years earlier, John Sedgewick had to practically drag his son James to begin work in Westwood pit at Honley in 1830. Once underground the boy soon disappeared and was not found for four days. He was in the old workings where his brother had been killed, hoping to die in the darkness rather than to have to work in the pit. (29). This may have been the extreme reaction of a frightened child, but real fear must have been experienced by many of the hurriers at some time.

Some children did not come from mining backgrounds. Abraham Lockwood, who started work at a pit at Lockwood at a tender age as a trapper, opening and closing ventilation doors, was the son of a cloth dresser and later was apprenticed to his father’s trade (30). An unknown proportion were pauper children, such as the eleven year old orphan Sarah Walker, who was killed when a stone knocked her out of a corve being raised up the shaft of Kaye’ pit at Overton. (31) In 1841, when there was much criticism of the New Poor Law and the way it was being administered in Huddersfield, there was outcry about a seven year old workhouse child who was put out as an apprentice to a Thornhill collier. The child weighed only 41 pounds and was so unfit for work that the collier had to send him back. (32).

The treatment of hurriers varied – but physical punishment was common. Sometimes a collier was prosecuted when he went too far, as in the case of one who belted a hurrier in Waterhouse’s pit at Lindley in 1849 or the Kirkheaton collier who assaulted one in 1864. A hurrier was almost “throttled” by a collier in an argument about a tub in a Lepton pit in 1868. (33) Colliers could also be protective towards their hurriers if others interfered with them. At Emley in 1856 an argument between two boys about the right of way in the gate resulted in one hurrier tipping the on-coming empty tub off the rails. He was consequently kicked by the other hurrier’s collier, although full tubs enroute to the pit bottom customarily had precedence. (34). A banksman was assaulted at Moorhouse’s pit at New Mill in 1857 by a collier whose hurrier he had allegedly “ill used”.

The hurriers were usually paid by their colliers. In 1854 at Sir J.L.Kaye’s Blossom Pit at Whiteley Upper the rate was nine shillings a week, while two years later a hurrier at Kirkburton summoned a collier for non payment of 3s.6d wages for three days work. In defence, the collier, adopting a “peculiar theory of the value of numbers”, claimed that the agreement was only for 1s.2d a day! (36). The hurriers’ wages compared well with the wages of children in local mills who might earn 4s.6d. to 7s.6d. a week. However, as bad as conditions were in mills and factories they did not approach the terrible conditions prevalent in collieries. No description can add anything to the eyewitness testimonies given to the Commissioners inquiring into child employment in mines in 1842, extracts of which are reproduced below. (Appendix A).

The pit is a dangerous as well as unpleasant and unhealthy environment and a wide variety of hazards confronted the children. The ever present threat of roof-fall claimed a 10 year old hurrier at Stansfield & Briggs’ colliery at Flockton in 1838. The following year two brothers aged 12 and 14 and their 16 year old sister were killed when the rope lowering them down the shaft in a corve broke, sending them plunging over 80 yards. (37). As well as such inherent risks, children could be placed in extra danger because of their lack of safety consciousness or through playfulness or fatigue. (38) At Joseph Haigh’s Woodsay Pit in 1848 a boy “in his eagerness to descend” missed his footing when stepping into a corve and fell down the shaft (39). A hurrier at Bradley Colliery in 1857 disobeyed orders and took a short cut down a steep gate with a corve holding about 2 cwt of coal which ran away with him, smashing his head against the wall. He died later in the infirmary. (40).

Other forms of indiscipline had fatal results. The hurriers at Kirkheaton colliery in 1839 used to play at swinging on the corves as they were being raised, then dropping off. One twelve year old boy left it too late and dared not let go until near the top of the shaft he could hold on no longer falling fifty yards. (41) Another game was played on the surface at Cliff Wood colliery at Brockholes where the boys used to ride on the corves down the incline of the tramway. One was injured in 1854. (42) Even when the pit was not working childish exuberance could have tragic results. A hurrier fell down the shaft of Kirkstyes colliery at Cumberworth in the same year although the pit was temporarily stood due to gas (43). The brutalising conditions of pit life must have contributed to unruly behaviour. In fact in 1867 fighting and such “insubordination” were so bad at Kaye’s Flockton colliery that it was claimed the hurriers had, “almost become unmanageable” Boys on the way to work at a Thurstonland pit in 1859 demonstrated their unruliness by stoning the train between Brockholes station and Stocksmoor tunnel.. One 12 year old was prosecuted and fined £2. (44).

As late as 1853 an 8 year old boy (the son of a shoemaker), was killed at Fieldhouse colliery where he was hurrying for his brother when the chair ascended without a signal. The inquest jury could only express disapproval at boys so young being employed in a pit. (45) But it was the employment of females underground, outlawed by the 1842 Act, which most roused public opinion and offended middle class morality. Conditions in local pits gave rise to one of the most graphic and oft quoted condemnations by the Commissioners.

“One of the most disgusting sights I have ever seen was that of young females dressed like boys in trousers, crawling on all fours with belts round their waists and chains passing between their legs at day pits at Hunshelf Bank and in many small pit near Holmfrith [sic] and New Mills…In two other pits in the Huddersfield Union I have seen the same sight. In one near New Mills [sic] the chain passing high up between the legs of two of these girls had worn large holes in their trousers and any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined than these girls at work – no brothel can beat it… In the Flockton and Thornhill pits the system is even more indecent, for though the girls are clothed at least three quarters of the men work stark naked or with a flannel waistcoat only and in this state they assist one another to fill the corves 18 or 20 times a day.” (46)

Although consequent to this inquiry female labour underground was abolished at least two local pits continued to employ girl hurriers. George Haigh, the Constable of Almondbury, warned James Whiteley to discharge his girls and he complied in March 1843. several months later Haigh learned that J.W.Moorhouse of Lidget [sic] pit at Wooldale was still employing girls. When he visited the day hole on 5 November he saw four hurriers come out with full corves who “he should not have known them to be females but for their hair, their dress being like that of boys.” The Holmfirth magistrates refused to hear the case since one member of the bench was a coal owner and the hearing at Huddersfield fined Moorhouse £5 on each charge. The girls, aged twelve, thirteen, fifteen and seventeen were said to be, “so deplorably ignorant that they knew not how long they had worked in the pit; they knew nothing of the month of November…” The collier who had initially informed Haigh said in court that he hardly knew them now that they were dressed up. (47)

The hurriers’ task was lightened by the introduction of ponies. These were working in the maingates of some pits by the 1840’s but locally they were not introduced into Hall Ing colliery until shortly before 1853. (48).

Despite the 1842 Act, the 1850 Act which instituted Mine Inspectors and the 1860 Act prohibitting boys under twelve from working underground (except those of ten or eleven who had a certificate of elementary education), mining remained a perilous occupation for children and adults. Death and injury came in many forms. After 1850 the inspectors adopted a basic classification of accidents which we shall follow. This grim catalogue of death and agony is not fully comprehensive, but it vividly illustrates the main tasks and the accompanying hazards encountered in mining.

OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS

Shaft Accidents

The earliest incident reported in the 19th century is one at a Lindley pit in 1803 when, witnessed by his two sons, the banksman fell down the shaft and was killed.(49). Riding up or down the shaft, or even working in its vicinity could be hazardous and some examples of the kinds of accidents which resulted have already been cited. In 1833 Martha Beaver was just passing the pit bottom of Law colliery at Hepworth when her clothing became caught in a corve that was being raised. She was half way up the shaft when the fabric tore, releasing her to her death .(50)

Another case involving the death of a banksman occurred at Clayton West colliery in 1838 when the pin slipped on the shaft of the gin horse, loosing the winding rope and sending the descending corve containing the banksman plunging 53 yards. Wrenched upwards, the ascending empty scoop smashed into the pithead gear, broke loose and plummeted back down onto the banksman, fracturing his skull. The inquest was held in the pub of the colliery owner, Tom Gelder. (51) Sam Sykes of Lindley was killed when he fell out of a scoop while ascending the shaft at Grimscar colliery in 1843. In 1855 the elder son of another publican, John Wagstaff of the Fox and Grapes owned Law colliery. His 18 year old brother was killed descending the 27 yard shaft when the rope snapped. He had recently been advised to replace it. (52)

That same year a Kirkburton boy was seriously injured when he fell 28 yards down a shaft near the church. It was the practice at the pit to stop the pumping engine after work on Saturdays and restart it the Sunday evening to prepare for work on Monday and he was being lowered on the clatch irons to check the depth of water. (53) Kirkburton was the scene of two more shaft accidents in 1867. In May the manager was tipped out of a tub while ascending a 60 yard, horse gin wound, shaft newly sunk by the manufacturer Wright Mellor. The following month at Seth Senior’s Darley Main pit one man fell when the engine slipped out of gear and the platform, from which three men were fixing stays near the top of the shaft, dropped suddenly. (54)

Another danger was posed by objects falling down the shaft. In 1838 George Walker died when a stone struck him as he was being drawn up a pit at Birchencliffe and, in the same year, ten year old Enoch Hirst was killed by a piece of coal falling down the shaft at Stansfield & Brigg’s Law Head colliery (55) A hurrier at New Ground pit near Kings Mill was luckier when he escaped with a broken thigh in a similar accident in 1846 (56). Several hundredweights of stone fell down the shaft of Jaggar’s pit at Shelley in 1850, crushing a 49 year old miner. (57)

A descending empty scoop injured a boy at Jaggar’s Emley Moor colliery in 1852 (58) and in 1857 a 12 year old hurrier was injured when the clatch irons slipped off a scoop which had just been raised to leave the pit top at Kirkstyes colliery. A similar accident occurred at the same pit a year later when a boy tried to hook on an empty corve while the banksman was busy. It was not secured correctly and plunged onto the hurrier below. (59)

However, it does not require a large object to kill if falling from height. A miner sinking a new shaft for C.Whiteley at Bradley Wood colliery in 1870 was struck by an object so small that the inquest could find no evidence as to what it was. (60)

Roof-Falls

Probably the most usual danger was the fall of parts of the roofs of underground roadways or workplaces. One collier lingered 13 weeks in Huddersfield Infirmary in 1850 with fatal injuries after being crushed in Haigh’s Whiteley Upper pit, while a collier was killed outright by a stone at Jaggar’s Emley Moor pit in 1852. (61). A miner escaped with a broken thigh at Sheard’s colliery at Lepton in 1856 and a foreman was killed by a large stone he unsuccessfully tried to secure with a punshon, or prop, near the coal face at Harpin’s pit at Thurstonland in 1864 (62). Roof-falls killed a 15 year old boy at the Hepworth Iron Co’s Millshaw colliery in 1865 and a collier at Stansfield’s Grange Moor pit in 1867. In the latter year a hurrier was injured by falling stone at Alderson’s Shelley pit. (63) Darley pit at Kirkburton suffered its second fatality in two years in 1869 when a collier was killed by a roof-fall (64). In Yorkshire as a whole in 1856 this was the most common form of fatal accident causing 13 deaths, compared with 9 resulting from falls down shafts. (65)

Firedamp

Another major category of accidents were those resulting from the explosion of firedamp or methane. This was an ever present threat when the main source of illumination underground came from candles. In 1833 a Flockton collier was killed when he broke into old workings and his candle ignited the released accumulation of gas. His son was badly burnt.(66) .That same year at a pit at Ainley Top owned by Sir Joseph Radcliffe an explosion killed five, including James Waterhouse, the lessee of the pit. One of the victims who lived long enough to tell the tale said that the ignition of gunpowder while blasting had come into contact with firedamp (67) At Whiteley’s New Ground colliery a collier and his hurrier were fatally burnt in 1840 despite the fact that men had complained of the danger for some time and one had even been sacked for refusing to work in that same place. Two people were injured in another explosion in this pit a few months later and the following year a collier was killed and others burnt. The victim, carrying a candle instead of a lamp, opened a trap door and was met by an inrush of gas. (68)

The early safety lamp was difficult to work by and after its introduction some colliers still preferred to use candles. In 1841 a collier at Emroyd colliery at Flockton removed the gauze from his lamp and he was killed along with three boys when a roof-fall forced a build-up of gas out of the goaf. The flames ran down the hurrying gate and a boy 100 yards away was injured (69). A collier was killed at Fieldhouse colliery in 1850 when he used a naked flame in defiance of instructions (70). Fieldhouse was the scene of a more serious explosion in 1853 which is dealt with in greater detail below since the inquest throws light on contemporary ventilation practices.

Other explosions recorded in our area include:

Holmfirth, 1839, a 14 year old boy killed;

Lockwood, 1840, two killed entering an area againstorders to fetch tools;

Briestwhistle, 1841, five killed due to the greasy state of one of the victim’s lamps;

Waterhouse’s pit, 1842, two killed and several hurt when the overlooker was testing for gas but the candle of a person following ignited it. His son was one of he dead;

Holmfirth, 1850, one killed entering an unused drift with a naked candle;

Emroyd pit, 1850, two killed. it was thought that a safety lamp may have been responsible.

Firedamp was also responsible for a death at Messers Haigh Emley Moor pit in 1848 when Ben Robinson 16, suffocated in old workings, while retrieving a ‘tomahawk’ he had left there weeks before. (Incidentally, this is the earliest reference to a miners pick, with a combined pick and hammer head, being referred to by this name. It was still called a ‘tommyhawk’ when the author was at Emley Moor in the early 1970s)’ A 14 year old boy at Jaggar’s Emley Moor colliery in 1851, was also indirectly killed by fire damp which caused him to pass out and fall from the corve as he was being raised up the shaft. (71)

Fortunately gas was less of a problem in local pits than in many others in the coal field or this toll may have been even higher.

Pit Top Accidents

Amongst the miscellaneous accidents are a number which occurred on the surface. Horrific injuries were inflicted on the banksman of Thurstonland colliery in 1843 wen he was screwing a nut on the steam engine which was still in motion. The key slipped and he fell into the fly-wheel race (72). At Whiteley’s colliery at Brockholes in 1860 the engine man was badly lacerated and his head nearly crushed by the upward stroke of the engine beam (73) In 1867 an accident occurred on the tramway at Linfit Lane when the banksman, acting as brakesman on a run of tubs travelling down the incline to the mill, fell off. (74)

These are only some of the accidents which came to the notice of the press and, at least prior to the keeping of records from 1850, there is no way of knowing what proportion of fatal accidents they represent. It must also be remembered that, given the standards of medical care available, even non-fatal cases involved much suffering. Hardship would result from long absences from work even for those who belonged to some friendly society or sick benefit club.

Disease

We also lack evidence for diseases resulting from working conditions, particularly respiratory ones, but also rheumatic and arthritic complaints caused by damp and wet conditions. In 1842 we hear of Tom Moore of Lindley, a former collier who died in “extreme destitution”. He was employed on relief work breaking stone despite appearing “asthmatic” and much addicted to spitting. His medication consisted of a concoction of pepper and spanish juice! Death was said to have been due to natural causes but the Halifax Guardian declared, “we shall believe that the untimely end of Thomas Moore is another instance of the murderous nature of the thrice accursed Poor Laws.” (75)

From the symptoms described it is possible that the “asthma” of Tom Moore was in act silicosis or pneumoconiosis caused by inhaling stone or coal dust. Premature death must have been a common fate for many colliers who had been in the pit since childhood.

MASTERS AND MEN

Against the background of these conditions it is not surprising that colliers were often individually obstinate or collectively discontented over various grievances. Coal owners, like other 19th century employers, dealt with this resistance with a combination of paternalism and coercion. The Masters and Servants Act could be invoked to prevent strikes, individual protest or lack of work discipline by prosecuting miners who left work without giving the statutory notice included in their contract of employment.

In 1836 a Flockton collier received two months and a Bradley collier one month in Wakefield House of Correction for “neglect of work”. (76) Joseph Jebson of Denby Grange colliery was summoned in 1841 by Kaye’s agent, Pickard for leaving work without notice, which, according to the contract should have been three months. He agreed to return to work on payment of the court expenses of 8s.6d. (77) Edward Beecher, Pickard’s successor, summoned Henry Parker for “absenting himself from service before contract completed and without giving proper notice” in 1854. Parker had left work previously then returned when he heard a summons was issued, promising to pay the expenses and work out the contract. However, after two weeks he gave Beecher two months notice and then left again just over a week later, having only completed ten full days of work in six weeks according to Beecher. Parker claimed in defence that the place he worked was too “foul” to earn enough, but he offered to return. Despite the magistrates recommendation Beecher refused to accept reconciliation and pressed for a conviction. Parker was fined 35s. or one month in the House of Correction.(78)

In 1859 a collier, John Holly, when summoned for not working to contract, having only worked half an hour one day, claimed he could not get a hurrier. His case too had been adjourned previously on his promise to return to work and this time he was sentenced to one month and a fine of 5s. The explanation of an 18 year old who left Kirkstyes colliery in 1866 without notice when he was refused a pay rise was that he was unable to read the rules posted up. (79)

Another case arose in one of Kaye’s pits later that year, this time for absenteeism and disobeying the “lawful commands of his masters agents.” At Blossom Pit at Whiteley Upper it had become the habit of the colliers working in the Cromwell seam – which was described as three feet three inches high and gassy – to abandon work early and go drinking, leaving the hurriers to get the coal. As there was no locks on the safety lamps it was dangerous to leave them with the hurriers unsupervised. One collier, James Parker, was summonsed as an example to the others since he had been warned several times about leaving his hurrier and for working with the top of his lamp off. One day when he tried to come out early he was lowered back down the pit three times, holding up work for an hour. Finally allowed to the surface, he threatened to hit the banksman with his lamp.

Parker was defended in court by W.P.Roberts, known as the “miners’ attorney”, who often offered his services to trade unionists and workers in dispute. His presence may indicate that there was more behind the case than that claimed by the prosecution. He stated the men’s complaint that sticks put on their own tubs for the banksman to record the amount of coal sent out were being removed, so that tubs were not accounted to them and wages were reduced. The hurriers did not do any coal getting as was alleged, they only brought the tubs to the pit bottom to the hanger-on. According to the colliery agent the men worked irregularly and wages varied from 4d. to 6s.10d a day, they could earn up to £1.6s.3d. a week out of which they paid 9s. to the hurrier and rent for their lamps and oil.

Such variations in wages however did not depend solely on the ability or motivation of the collier, but also on the conditions in the workplace affected by such factors as geology, water, gas, etc. We hear from other areas of employers making deductions or cutting wages by various devious means. The removal of the tally sticks from the tubs at Blossom pit may indicate that some malpractice was indeed taking place. One of the recurring demands made by miners before 1870 was for checkweighmen to ensure that the output of each man was correctly recorded on the pit top. In this case the master’s version was accepted by the magistrates and James Parker was sentenced to fourteen days in the House of Correction. “That’s nothing,”, he replied, “I could stand on my head that time.” (80).

Although workers had to give notice they could often be summarily dismissed by the masters. In 1853 an incident arose when George Swallow was sacked by the banksman at Charles Whiteley’s Bradley Wood colliery for causing a disturbance. When Swallow came to hand in his tools and ask for his due wages he was told to go back down the pit and fetch a hammer and shovel he had left. Returning with them he flung them into the pit top cabin and threatened to assault the banksman. As a result he was summonsed and the court told he was “a complete outlaw in the pit and a terror to the other men.” (81). Sometimes, however, the law was favourable to the employees. After he was dismissed by Alderson of Shelley, Crawshaw Green took out a summons for 7s.4d. wages owed to him. In defence it was stated that Green had handed-in his tools at the pit, not at the office in Kirkburton. The magistrates ruled that since there was no bylaw posted at the pit to this effect Alderson had to pay up, plus court costs.(82)

Masters did not just rely on legal or economic coercion to ensure the loyalty of the workforce and impose labour discipline. Some tempered authority with consideration and maintained customs intending to show that he interests of masters and men were the same and the good of the firm was paramount. Landowners like Kaye extended their squirearchic paternalism of the estate community into the workplace. A common institution was the colliers’ treat and the first of these we hear of locally involved Kaye’s colliers at Denby Grange in January 1820. Although this was a time of widespread political and social unrest, including attempts to form a colliers’ trade union, the Denby Grange colliers drank a loyal toast, “The health of the King and Success of the Coal Trade.” By implication this was also a declaration of loyalty with their employer.(83)

There were treats at Moorhouse’s colliery at Wooldale in 1843, at Pickard & Stockwell’s in 1850 and at Craven & Co.’s in 1864. Obviously not all treats came to the attention of the press. Nor would many of the other joint celebrations of employers and miners, such as coronations or other political events or rites de passage of the employer’s family – births, comings-of-age, marriages or deaths. An example was reported in 1860 when the iron-stone miners and colliers of Hepworth Iron Co. demonstrated their affection when 200 marched to a funeral service at New Mill for William Dyson, one of the firm’ proprietors. (84) Benign gestures by employers did not always imply deferrence in the workforce. Whitely & Co.’s colliers continued on strike in 1844 despite the gift of a barrel of ale and £1 to buy food.(85)

TRADE UNIONS.

Unlike the textile workers of the Huddersfield neighbourhood, miners are notable by their absence from working class political movements of this period. This may be attributable to a number of factors – the brutalising conditions of work, the control of the masters outlined above, relatively good pay (at least in times of thriving trade) and the dispersion of miners in communities where weavers were more numerous and with whom they had limited contact. A Thornhill miner was transported for life and two Breistwhistle miners hung for burglary during the Luddite disturbances of 1812 but it is clear from the trial that they were using Luddism as a cover for common crime.(86) In 1820 however at least one collier, Sam Sharpe of Colne Bridge, was involved in the preparations for the uprising that year (87). There is no mention of miners participating in the radical agitation of the early 1830s nor in the Chartism which succeeded it.

Similarly trade unionism was not deeply rooted among local miners and the initiatives for its organisation appear to have usually come from outside the area. In 1819 when a Miners’ Union was being successfully organised around Leeds and Dewsbury, miners in our area, or at least its northern periphery, may have been involved. John Robinson of Calder Main colliery and John Goodair of Flockton colliery were committed to York Castle for three months for unlawful combination and intimidating others to join. (88)

Following the legalisation of trade unions in 1824 there was an upsurge of activity from 1830 to 1834 in many trades, but little evidence in our area for the involvement of miners. There was certainly militancy in surrounding pits connected with the Leeds based general union nicknamed “John Powlett”. A strike at a colliery at Ossett is recorded and a miner from Elland was prosecuted for delivering a letter to an Ossett coal owner threatening a strike. The Whig parliamentary candidate in the Huddersfield election in 1832, Captain Fenton, reported that the workers of a local “master collier” had been “obliged to leave him by the orders of the Union – though they said they had worked for him for many years and were satisfied with both his treatment and their wages.” (89)

The repression of this union was greeted with relief by the employers and their mouthpiece, the Whig Leeds Mercury of 5 July 1834, published a satirical report from a local correspondent apparently referring to trade unionism among miners;

“Interred at Meltham in a coal pit, John Powlett who has, in times past been much esteemed, but his payment not being as good as was expected he lost his credit and his mind has been very strange low spirited and worn away and the white sheep thought it best to bury him and drop the name altogether, which they did and get everyone a jug of ale with their old masters and all separated in peace and good order.”

During the August of 1842 there was a general strike throughout the industrial areas of Lancashire, Cheshire and Yorkshire as thousands of workers marched across the countryside losing down workplaces – the so called “Plug Plot”. Haigh’s colliery at Hall Ing, Honley and pits in the vicinity of New Mill were stopped from working as, no doubt, were others along the line of march of the strikers. How willingly local miners joined is not recorded although at least one, Samuel Howarth of Flockton, (if he is the coal miner of that name recorded in the previous years’ census) played a prominent part in spreading the strike, including stopping Norton’s factory at Scissett. Due to lack of co-ordinated trade union or political leadership and because of brisk repression by the authorities, the strike movement petered out. (90).

By the end of December 1843 however, the Miners’ Association, the first national miners’ trade union to achieve even transitory success, was recruiting in the area. On 27 December a meeting at Honley was addressed by William Holdgate of Colne in Lancashire (a Chartist strike leader in 1842) and 31 colliers took out membership cards. At Meltham he found that ” The men of this place are threatened by their employer to be dismissed from their employment if they joined the Union but everyone of them was enrolled, notwithstanding.” At Lockwood a few more joined. (91) By the time of the delegate meeting at Barnsley on 2 March the subscriptions from the Huddersfield area roughly indicate the relative local strength of the union; Lockwood £1.9s.8d; Lepton £1.3s.3d.; Elland 18s.8d.; Cliff Birchin [sic] 15s.3d; and Meltham 5s.11d. (92)

The Union was encouraged by the Chartists and Feargus O’Connor’s national newspaper the Northern Star, published in Leeds, printed reports on the progress of the Miners’ Association. The Honley meeting referred to acknowledged its thanks to the Star and the delegate meeting at Barnsley agreed on a penny a week extra subscription to help the Victim Fund to help Chartist prisoners arrested after the previous year’s strike. The unionisation of miners was thus also assisting the spread of political ideas amongst them.

At the beginning of May 1844 the miners of Yorkshire put forward their demands. On 7 May delegates from local pits met at the White Hart in Huddersfield under the chairmanship of George Kinder of Lepton in order “to advise on the best means to adopt to ensure the benefit of both masters and men.” Although invited, no masters attended the meeting and delegates from the various pits reported that none had consented to the requested wage increase. It was agreed that the “bylaws” of the Miners’ Association be submitted to the masters and, if they did not accept the conditions, that a strike be called. Tom Shepherd and the Association’s secretary David Swallow, exhorted the meeting “to be sober, to support the Union, to work rather less and to think more instead of letting others think for them.” They warned that the miners would be generally abused in the press in an attempt to create dissension, but, if they “stood by their order” they would prevail. (93) Over the following week Tom Shepherd carried this message to meetings in the Honley, Huddersfield, Dewsbury and Dawgreen areas. (94)

The first strike broke out at Clarke Whiteley’s Commonside colliery at Lepton. As well as a wage demand there were “other grievances such as the discontinuance of home coal”, that is coal allowed the miner for his own use. After a month the men returned with the wage advance and presumably other demands conceded.(95) At Stockwell’s “extensive mines” at Grange Moor the men won a 4s.6d a week increase, or 5d. a ton. The masters increased their prices by 6d. a ton to more than compensate for the rise. Improved wages were also won at Kitson’s colliery at Whiteley. (96)

The strikes invoked a lot of sympathy. The radical Leeds Times thought that the public would rather pay more for their coal “than that such a hard toiling and deserving class of men should be denied the comforts ad even necessaries of life.” Miners who were still working, as well as other workers, contributed to the strike fund and an acknowledgement was published in the Star of 29 June;

Huddersfield – The miners of this district beg to return their thanks for the following sums – Mr David Shaw’s Factory, Honley £1.7.0d.; Elland Society, £1.9.6d.; Mr Thomas Moorhouse colliers, 6s.; Rock Inn Society,1.4.0d.; a few Odd Fellow Lodges,10.2d.; Messers Tinkers’ colliers, 8s.; Mr Sergeant Marshall, retail brewer, 5s.; a few friends at Berry Brow, 15s.9d.; and sundry small sums amounting in the whole to £8.12s.

Over the following weeks, Wood’s worsted factory at Clayton West, Clarke Whiteley’s colliers and the Huddersfield tailors made donations.(97) By July the local campaign had concluded successfully and it was reported that there was not a colliery in the Huddersfield district working at the old wages. Waterhouse & Co. of Birchencliffe, Tinker & Co.; Haigh & Co. of Flockton and Emley Woodhouse and Haigh Bros. of Flockton Moor were among those who had conceded. (98)

Strikes were more protracted in other parts of the country and met with bitter opposition. Support for the miners continued and it was reported from Huddersfield in August that “The trades of this town are rousing to the assistance of the miners of the north.” (99) The local victories had boosted the Miners’ Association and the committee meeting at the Griffin Inn at Wakefield in July was in receipt of several subscriptions from the Huddersfield area. (100) In October David Swallow was addressing “very successful meetings” in Lepton, Lockwood, Honley and Birchencliffe.(101)

The fortunes of the Association were no so bright in other parts of Yorkshire or in other coal fields where the masters successfully broke strikes. .Its decline was less newsworthy than its rise. This is reflected in the laconic conclusion of the chapter dealing with the county in a modern account of the Miners’ Association, ” A general delegate meeting was held at the Punch Bowl, Beeston, on the 5th July 1845. After that the Miners’ Association appears to have become extinct in Yorkshire.” (102)

It was not until 1853 that we hear again of a strike at a local colliery. In January the colliers at Hall Ing walked out against a 2d. per dozen reduction for coal getting, although some resumed work within a few days. It was said that the cut had been provoked by one of the men commenting that he would rather work on the Soft Bed for 2d. a dozen less than work on the Hard Bed. The outcome of this dispute is not known. (103) Another strike over different wages for working different seams occurred at Tinker’s colliery at Meltham in June when the men demanded 4d. a dozen more for working the thinnest of the two seams (104). The following week, John Alderson’s colliers at Shelley arrived at work on a Monday morning uneasy about a vague promise of a wage rise and were persuaded to go down the pit. However, after an underground meeting they decided to go home until a firm offer of a 6d. a dozen increase was made. The sight of carts turning away empty from the pit was supposed to have helped Alderson make up his mind to agree.(105)

1853 saw an improved market and higher price for coal. Indeed at the beginning of the next year the “rapid advance in price” was held responsible for the increased thefts of the commodity around Huddersfield (106). After almost a decade of indifferent to bad trade in the industry, the miners hoped to reap some benefit from their strengthened economic position and a trade union was re-establish. Some miners from the area may have joined since there is a reference to a delegate from Huddersfield at a meeting at Wakefield on 12 September. (107)

Unionised or not, there was a strike of colliers at Haigh’ new pit at Brockholes where 4d. a dozen for coal getting and 2d. a yard for straightwork was demanded. They were presently receiving 8d. a yard for straightwork but the height of the roadways varied from thirty inches in the twenty one inch seam to thirty three inches in the sixteen inch seam. Haigh told a deputation – which agreed with some of his points – that the rate for straightwork had always been the same and that 4d. a dozen increase for getting had been given two years before. He claimed that the men could earn 24s to 26s a week and nothing had been stopped from their wages even though ponies had been recently introduced to help the hurriers. The men returned at the old wage but with an extra 2d. for straightwork where necessary. (108)

The following decade saw the decline and revival of the West Yorkshire Miners’ Association (WYMA). In April 1864 the 75 men and boys at Stansfield & Co.’s Lane End colliery at Lepton struck against a 1d. reduction for getting and the loss of 1s.6d. “prize money”, or bonus, for every 20s. earned. They claimed that they had “long submitted to rules which would not be endured in any other district in the kingdom.” including a 4d. a day fine for absenteeism, even if it was due to illness.

After meeting with William Brown, a leader of the WYMA, the miners joined the organisation, a move which appeared to “irritate the employers”. Supported by funds levied from WYMA members at other pits and from money collected at religious camp meetings, the men held out until August. The employers refused the compromise that the men would seek no advance of wages for six months if the old wages were restored but they conceded that the men could remain in the union if they returned to work and accept a small reduction. The WYMA continued its attempts to organise the area and in October a meeting of miners at Kirkburton was addressed by Brown.(109).

The hostility of some masters to trade unions was renowned. Edward Brooke of Fieldhouse colliery, a leading methodist preacher, about this time received demands from his colliers which he dismissed as “unreasonable and unjust”. They consequently “turned out, to the embarrassment of their employer, who sought help in God…” So it was perhaps acting on the advice of the Almighty that some strikers were sacked. (110)

FIRE AND FLOOD

Squire Brooke’s beliefs had even more tragic results on another occasion. The colliery and adjacent clay works at Fieldhouse, just off Leeds Road near Huddersfield, was managed by his son, Edward jnr. By 1854 young Mr Edward was also head of Victoria Pottery on Leeds road as well as having other more extensive business interests. In that year for instance he was recruiting miners, navvies and brickmakers to work in a new mine of the Mersey Coal Co. in Van Dieman’s land. Seventeen men were sent off from Huddersfield station with a band playing “The girl I left behind me” and other suitable tunes. (111). The fact that such large and respectable employers could ignore basic mine safety demonstrates the prevalent standards of the time.

Out of deference to his father’s wish that men should not work on the Sabbath, Edward Jnr. directed that the ventilation furnace at Fieldhouse colliery should not operate between Saturday night and Monday morning. On the morning of Monday 20 June 1853, when about 50 men and boys were working, an explosion occurred in the Hard Bed killing two hurriers, John Haigh aged eleven and John Hiley, fourteen and injuring sixteen year old John Furniss and John Boothroyd. At the inquest the bottom steward, Samuel Clegg, a 45 year old barely literate collier who had been promoted four years previously, said that fire damp had not been known in that seam before. Air was drawn in through a day hole near the canal along airways, which were four feet by four feet and it was not thought necessary to use safety lamps. He conceded that the explosion would not have happened if he had tested the workplace with a lamp, or if the men had used them.

A collier, James Clarke, confirmed that he too had never known fire damp, although there was sometimes blackdamp present. There had been a good wind only fifteen yards away from where he was working on Saturday. When they were driving “slips” they might be several days out of an airway and no air pipes or brattices were used to direct air to them. Another collier, James Astley, said he worked with a candle unless specifically told by the steward that it was unsafe. If he had occasion to use a safety lamp it was kept locked and he didn’t interfere with it since he didn’t know how they worked. The pit blacksmith was in charge of the safety lamps.

In his evidence, the Mines Inspector condemned the standard of ventilation. The whole system was badly designed and was two miles long when it need only have been five furlongs. Air circulation was inadequate and there could have been little current if the furnace had been stood all day Sunday. Stopping the furnace was “a practice in the highest degree reprehensible [and] pregnant with danger.” The inquest verdict squarely blamed Brooke’s failure to keep the furnace working continuously and the lack of inspection by safety lamp, but there is no reference to any penalty being imposed. (112)

Three years after negligence was also blamed for a very different accident at Henry Ellis & Co.’s Kirkstyes colliery at Cumberworth. At Kirkstyes a six foot seam (including two bands of muck) was worked from two shafts, the south one, operated by a horse gin, was 250 yards up a one in eight gradient from the north shaft where there was a steam engine for winding and pumping. To the west were old workings, drained by a drift, which had been broken into about sixteen months earlier. It was decided to work below these old workings in the belief that they were at least six yards above.

On Saturday 19 April, a collier, Joseph Hanson, who had been working in that particular benk for nearly two months, saw a stream of clean water appear. It rapidly became a torrent and the north end of the pit was flooded, drowning John Turner Noble aged 12 and William Peel, 18. About 26 others escaped. As a crowd gathered at the pit bank awaiting the recovery of the bodies, the speed of the steam engine, which could raise ten gallons of water at a stroke, was doubled. By Tuesday the water level had dropped by five yards and by Friday the pit was back in working order. At the inquest Joseph Hanson said he had never seen boring rods used in the pit and the Mines Inspector quoted Rule 47 of Huddersfield District Collieries;

When headings, board gates or levels are approaching old works the under viewer or the deputy must order safety lamps and horizontal boring rods to be used so as to guard against a sudden irruption of gas or water.

Although Ellis had belonged for a month to the Colliery Masters’ Society which had drawn up the rules, he had not posted them in his pit. Both he and the bottom steward were severely reprimanded but the verdict was nevertheless “accidental death”. A month later Ellis was prosecuted for not displaying the rules. (113)

This lack of supervision, combined with ignorance and complacency, was evident in an accident at Messrs Haighs’ Sinking Wood pit near New Mill in 1870. A boy was killed after entering with a candle part of the workings which had not been inspected for gas. The underground ‘viewer’ was only partly literate and had three pits under his supervision which he was unable to adequately inspect every day. (114)

These local incidents were only a fraction of the hundreds of lives lost before parliament accepted the need for the 1855 Act which laid down the basic regulations for collieries and the 1872 Act which issued certificates of competence for colliery managers and stipulated that daily inspections of pits should be made. Even this latter law was not passed until the terrible explosions at Lundhill near Barnsley in 1857, which claimed 189 victims and Oakes colliery, also near Barnsley, in 1866 when 361 died.

EPILOGUE.

The introduction of the 1872 Mines Regulation Act and of the 1871 Criminal Law Amendment Act and Employers and Workmen Act which improved legal protection for Trade Unions, laid the foundation for the amelioration of conditions in collieries. The greater stability of union organisation in turn provided the pressure for further legislation to improve safety and wages. The 1870s also saw the first tentative steps towards mechanisation with the introduction of coal cutting machinery and later of haulage engines. (115)

However this did not mean conditions change overnight, and for the small collieries in our area, at least for those not already worked out, they continued to be arduous and dangerous. Accidents remained commonplace and miners still had to struggle to maintain wage levels. Wage disputes occurred in Shelley, Kirkburton and Holmfirth in 1872 and 1873 for example. Breaches of the 1872 Act are recorded at Shuttle Eye, Lepton, in 1877, where no qualified manager was employed, and at Six Lane Ends, Emley Moor in 1889, when the owner failed to ensure proper ventilation roads since he ‘did not wish to incur expense’ (116)

Small drifts continued in operation in the Holme Valley until the 1930s. One collier, Harry Moorhouse of New Mill who said he had begun work at six years of age in 1855 (although the 1842 Act made this illegal) was still working in a day hole in 1931 when he decided to retire after his 83rd birthday. After the owners had ceased business in 1890 he continued to work the drift as a one-man operation. The true ‘independent collier’.(117)

A GLOSSARY OF MINING TERMS USED

Banksman – man on pit bank, or pit top, who is in charge of the lowering and raising of materials and personnel up and down the shaft.

benk – method of working a colliery by driving long wide galleriesinto the seam seperated by walls of coal (See Diag. )

blackdamp – or chokedamp, carbon dioxide.

board – main underground roadway.

brattices – wooden panels or heavy fabric used to direct the flow of air underground.

Chair – or cage, lift on which people and corves or tubs are conveyed up and down the shaft.

Checkweighman –man chosen by the miners to ensure that their output of coal is correctly recorded at the pit top.

clatch/clutch irons -device on end of winding rope to which chair or scoop was attached.

day hole – mine where access is not by vertical shaft but by a tunnel or drift.

firedamp methane, natural gas.

gate an underground roadway.

goaf/gob – area where coal has been extracted from seam and the roof has been left to subside.

Hard Bed – one of the main seams in the area, along with the Soft Bed, both being relatively near the surface and outcropping in some places.

punsheon – Wooden prop used to support roof as coal is being got.

Safety lamp – Oil lamp in which the surrounding air is prevented from coming into direct contact with the flame by a copper gauze and later also a glass, preventing the flashpoint which could ignite methane.

straightwork – the opening up, or driving, of underground roadways.

PERSONAL ACCOUNTS OF CONDITIONS IN LOCAL PITS IN 1842

Mary Holmes Aged 14. Mealhill pit, Hepworth.

I have been eight years working in pits. I have always hurried;I never thrusts you saw me with a belt round my waist and the chain through my legs. I hurry so in the board-gates. I always wear lad’s clothes. The trousers don’t get torn at all. It tires me middling; my back doesn’t ache at all, not my legs. I like being in pit and don’t want to do nought else; I never tried to do anything else. Sometimes I get cold by its being so wet; the wet covers my ankles. Sometimes I stop and fill the corves after the getter is gone. I don’t know how long I shall stop in the pit. I am sure I’d rather be in the pit where I am thrashed sometimes than do anything else.

Ebenezer Healy Aged 13.

I went into the pit to help before I was five years old. I used to thrust; I didn’t do it long. I hurry now with a belt and chain in the board-gates. there are no rails there. We have to hurry full corves this way, up hill as well as down. I do this myself and I have sixteen runs a day for which I have one shilling. Our breeches are often torn between the legs with the chain. The girls’ breeches are torn as often as ours; they are torn many a time and when they are going along we can see them all between the legs naked; I have often; and that girl, Mary Holmes, was so today; she denies it, but its true for all that.

Margaret Gormley,aged 9, Messers Waterhouses’ pit, Lindley.

I have been in the pit thrusting corves about a year. There are two other girls working with me. I’d rather lake than go into the pit. I’d rather set cards than go into the pit. They flog us down the pit; sometimes with their hand upon my bottom which hurts me very much; Thomas Coppland flogs me more than once a day which makes me cry.

The Sub-commissioner comments;

I descended this pit accompanied by one of the banksmen and, on alighting at the bottom, found the entrance to the mainway two feet ten inches [high] and which extended 500 yards. The bottom was deep in mire and, as I had no corves low enough to convey me to the workings, waited somtime under the dripping shaft the arrival of the hurriers, as I had reason to suspect there were some very young children labouring there. At length, three girls arrived with as many boys. It was impossible in the dark to distinguish the sexes. They were all naked excepting their shifts or shirts. Having placed one in th corve I gave the signal and ascended. On alighting on the pit bank I discovered it was a girl. I could have not believed that I could have found human nature so degraded.

Susan Pitchforth, Elland,Waterhouses’ pit.

I run 24 corves a day; I cannot come up until I have done them all. I’d rather set cards than work in the pit.

The Sub-commissioner comments;

She stood shivering before me from the cold. The rag that hung about her waist was once called a shift, which is as black as the coal she thrusts and saturated with water, the drippings of the roof and shaft. During my examination of her the banksman whom I had left in the pit came to the public house and wanted to take her away, because, as he expressed himself, it was not decent that her person be exposed to us; oh no! it was criminal above ground; and like the two or three colliers in the cabin he became evidently mortified that these deeds of darkness should come to light.

William Pickard, Steward to Sir J.L.Kaye.

I have known a married woman hurrying for man who worked stark naked and not any kin to her.

Margaret Westwood,14 Emroyd colliery,Flockton (Stansfield & Briggs)

I hurry for Charles Littlewood; I am let to him,he is no kin to me; he works stark naked; he has no waistcoat nor nothing.

George Hirst,32,collier,Gin Pit,Low Common (Kirkburton,Stansfield & Briggs)

The children hurry with belt and chain, the chain passing between ther legs, girls and all. It privilege some poor folks to bring their girls to pits and I have seen many who have made respectable women and, for ought I know, useful wives. I don’t know that girls have more impudence than the other girls that are brought up in other ways. It is true that they all have impudence.

Commissioners Report on Employment of Children in Mines 1842,pages 25 para.122;,p.77,para.320;p.79,para.327.

REFERENCES AND NOTES.

1. Almondbury Parish Registers, 28 Mar,25 Jul 1574; 12 Mar,29 Sep 1575.

2. D.H.Holmes, The Mining and Quarrying of Huddersfield and District (Huddersfield 1967)p.23.

3. Almondbury Parish Registers, 13 Oct, 13 Dec 1605, 6 Apr. 1651 (Tom Shaw and Robert Haigh.

4. Holmes op cit. p.23.

5. Ibid.

6. G. Redmonds,’ Mining and Coal Getters ‘Huddersfield Examiner (HE) 22 Oct 1983.

7. Leeds Mercury (LM) 16 Nov 1779.

8. LM 4 May 1784.

9. Land Tax Returns, County Record Office, Wakefield.

Kirkheaton. 1783.R.H.Beaumont’s Land, Jonathon Haworth coal pits;1792 Wm. Stancliffe coalpits; 1801 Widow Stancliffe coal pits.

Honley 1788. Earl of Dartmouth’s colliery; 1793 John Lockwood colliery.

Farnley Tyas 1788. George Jaggar colliery.

Almondbury 1781.Sir John Ramsden’s Land, John Bradley and Mrs Crowther coalpits,Jos.Jaggar coal pits;1788 Mr Crowther & Co. coal pits.; 1790 Wm Bradley coal pits.

Fulstone 1782, Jos Charlesworth coal pits, Jos.Armitage coal pits;1785 William Newton coal pit;1794 Beaumont Esq Land, Nathaniel Berry coal pit; 1803 John Bates, Butterly coal pit.

Huddersfield 1789 Ramsden’s land, Jos Bradley coal pit.

Kirkburton 1785.Edmund Jessop coal mine; 1787.Sir John Kaye’s land,Messers Milnes & Jaggar coal mine.

10. Dartmouth Estate Terrier 1805, Estate Office, Slaithwaite.

11, LM 8 Feb 1806.

12. LM 12 Feb 1806.

13. Huddersfield Chronicle (HC)7 Dec 1867.

14. Census 1851.

15. HC 18 May 1867;HE 9 Aug 1854, Two fancy weavers, seeking coal in a disused dayhole of Norton were suffocated by gas.

16. Census 1851.

17. See below,.Tom Gelder and John Wagstaff. Also in 1841 Halifax Guardian 1 Oct Elijah Clifford of the Shepherd’s Arms lost his license when he was stranded in the pit bottom at Grimscar by a winding engine breakdown and was unable to attend the brewster sessions. Another publican, Ben Lockwood of the Blacksmiths Arms was the proprietor of Shuttle Eye colliery,Huddersfield Weekly Examiner HEW 8 Nov 1883.

18. M.A.Jaggar History of Honley (Huddersfield 1914) p.298.

19. HE 17 Jun 1856

20. HC 25 Aug 1860.

21. HC 24 May 1862.

22. Holmes,op.cit. pp.31-33; E.Baines Yorkshire Past and Present.

23. For the geology of the area see Holmes,op.cit. and Institute of Geological Sciences,Britsh Regional Geology:The Pennines and Adjacent Areas (HMSO 1954) Chapter VI.

24. R.L.Galloway Annals of Coal Mining and the Coal Trade ( orig.1904,David & Charles reprint 1971) Vol II Chapter XIX.

25. HC 23 Jan 1864.

26. Parliamentary Papers 1842 XV Inquiry into the Employment of the Children of the Poorer Classes in Mines and Collieries.

27. Thornhill Parish registers 1699 Sep 7.

28. F.Machin,The Yorkshire Miners (Barnsley 1958) p.215.

29. LM 15 May 1830.

30. F.Jewell,Little Abe,The Bishop of Berry Brow, (London 1880) pp.24-26

31. HG 27 Mar 1838.

32. Northern Star (NS) 6,Feb,13 Feb 1841; HC 12 pr 1862,Huddersfield Board of

Guardians discussed whether parish apprentices should be put out to journeyman colliers, (i.e.working colliers) or only to masters. The Rev. Hulbert stated “if boys were to be employed in collieries at all then paupers ought to be employed and he thought it was spurious humanity to say that a pauper child should not be apprentice to a collier.”

33. LM 31 Mar 1849;HC 29 Oct 1864; HE 25 Apr 1868.

34. HE 9 Feb 1856.

35. HE 3 Jan 1857.

36. HE 4 Nov 1854; HE 1 Mar 1856.

37. Leeds Times (LT) 2 Feb 1839; Northern Star 7 Apr.1838.

38. In 1972 the International Labour office listed special factors which make youth and children more prone to industrial injury:

a) Ignorance and curiosity.

c) Desire to show off.

d) Contempt for safety first.

e) Liability to fatigue.

f) Boredom leading to horseplay.

39. LM 4 Nov 1848.

40. HC 10 Jan 1857.

41. LT 24 Aug 1839.

42. HE 25 Feb 1854.

43. HE 5 Aug 1854.

44. HC 16 Feb,2 Mar 1867;HC 23 Apr 1859.

45. HE 15 May 1853.

46. PP 1842 XVI,p 181, sub-commissioner Symon. The question arises, was the commissioner’s knowldge of brothels as wide as that of collieries?

47. NS 6 Jan 1844; Angela J John, By the Sweat of their Brow:Women Workers in Victorian Coal Mines (London 1984) Ch.1 and 2 for general background

48 HE 12 Nov 1853.

49. LM 8 Oct 1803.

50. LM 1 Jun 1833.

51. LT 10 Nov 1838.

52. LM 26 Aug 1843. HE 27 Oct 1855.

53. HE 28 Jul 1855.

54. HC 18 May, 27 Jun 1867.

55. NS 3 Feb 1838.

56. LT 24 Oct 1846.

57. LM 15 May 1850.

58. HE 4 Jun 1852.

59. HE 13 Jun 1857;HE 12 Jun 1858.

60. HE 26 Feb 1870.

61. LM 1 Jun 1850; HC 11 Dec 1852.

62. HE 25 Oct 1856;HC 16 Jan 1864.

63 HE 14 Jan 1865;HC 27 Jun 1867;HC 7 Dec 1867.

64. HC 10 Jul 1869.

65. HE 7 Nov 1857.

66. LM 13 Jul 1833.

67. LM 1 Jun, LI 8 Jun 1833.

68. NS 22 Aug 1840;NS 11 Dec 1841;Galloway,op.cit. p.60.

69. Ibid.p.59.

70. LM 9 Nov 1850,Less than two yers later, James Ellam of Kirkburton the father of the victim Charles Ellam. was killed in Haigh’s colliery at Flockton Moor when the winding rope slipped while he was descending the shaft to inspect a chimney from an engine in the pit bottom. He left a widow and seven children. HC 1 May 1852.

71. Galloway,op.cit. Chapter VI; LI 18 Mar 1848; HC 27 Sep 1851..

72. LT 9 See 1843.

73. HC 25 Aug 1860.

74. HC 19 Jan 1860; HC 7 Dec 1867.

75. HG 1 Jan 1842.

76. HG 7 May 1836.

77. HG 6 Nov 1854 78. HE 4 Nov 1854.

79. HE 12 Nov 1859;HE 25 May 1866.

80. HE 4 Nov 1854.

81 .Disputes between the men themselves were not uncommon. In 1848 a Grange Moor collier was prosecuted for kicking another whilst at work.LM 12 Aug 1848.

82. HE 18 Apr 1868.

83. Leeds Intelligencer 3 Jan 1820.

84. NS 6 Jan 1844;LM 19 Jan 1850; HC 31 Dec 1864; HE 21 Ar 1860.

85. LT 15 Jun 1844.

86. Poceedings of the York Special Commision 1813, trial of John Lumb, John Swallow, Joshua Fisher.

87. Public Records Office, treasury Solicitor’s Papers,TS.11/1013.Deposition of Edmund Norcliffe et.al.

88. LM 24 Dec 1819.

89. Machin op.cit p.38; Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments (Sheffield City Library) g.9.2. Charles Ramsden to the Lord Leiutenant 11 Aug 1832.

90. LM,NS,LT,HG 27 Aug to 10Sep 1842 passim.

91. NS 6 Mar 1844.

92. NS 9 Mar 1844.

93. LT 11 May 1844.

94. NS 18 May 1844.

95. NS 25 May;LT 15 Jun 1844.

96. LT 1 Jun,15 Jun 1844.

97. NS 27 Jul,17 Aug 844.

98. NS 20 Jul 1844.

99. NS 17 Aug 1844.

100. NS 13 Jul 1844, the list includes:Lepton Lodge,£4.13s;Huddersfield £3.15s.3d.; A few friends at Emley Moor 10s.0d.; Emley Woodhouse colliery 14s.0d.;Briestfield,£1.14s.0d.; Flockton District, £2.14s4d.; Friends at Lepton,1s.5d;Friends at Dalton,2s7d;Friends at Huddersfeld 8s.8d;Friends at Clayton,3s.6d;Friends at Kirkheaton 4s.6d.

101. NS 5 Oct 1844.

102. R.Challinor and B.Ripley The Miners’Asociation: A trade union in the age of the Chartists. (Lawrence & Wishart 1968) p.166.

103. HC 22 Jan 1853.

104. HE 18 Jan 1853.

105. HE 25 Jun 1853.

106. HC 14 Jan 1854.

107. Machin,op.cit p,70.

108. HE 12 Nov 1853.

109. HC 9 Jul,22 Oct 1864; Machin op.cit. p.129.

110. J.H.Lord, Squire Brook p.236

111. HC 15 Apr 1854.

112. E 25 Jun 1853.

113. HE 26 Apr 1856.

114. HE 4 Jun.!870.

115. Stanley Jevons. The British Coal Trade (1915,David and Charles reprints 1969).

116. HEW 26 Oct 1872, 4 Jan, 8 Mar 1873;,10 Feb 1877, Wakefield Express 29 han 1889

117. HE 6 Nov. 1931; Royden Harrison,Independent Collier:The Coal Miner as Archetypal Proletarian Reconsidered (Harvester 1878) he diversity of mining conditions in the Huddersfield area supports the thesis of this book that there is no ideal type of miner. It is a part of the coalfield and a type of small scale mining which has received scant attention, see for example, John Benson, British Coalminers in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History. (Longman 1989); R.Church, History of the British Coal Industry (Oxford 1986).

Hi

Just to let you know ‘Law Pit’ and ‘Oxlee Pit’ are separate mines with the Oxlee colliery near the property called ‘Oxlee’ at a lot lower level. They might all meet underground like most mines did.

Roger Lynch

I remember as a teacher researching and finding evidence of women and children down mines. There was a very good recording of actors reading what actual miners said. It was very poignant and repugnant, and includes workers in the factories as well and how they were treated. One story I found at the Library was of a woman who went down a Huddersfield mine near where ICI used to be, and had her baby down there, which she brought up alive. Women and men wore hardly anything because of the heat and they would pull and push containers like beasts of burden. Cynthia Allen McLaglen

Hi Her comments fit in with what we know already about the coal mining. I assume that she is talking about the Grove Pit which I brought up in my lecture. I am working with a chap at the moment who lives round this area and Fieldhouse Pit, and he is coming up with all sorts of things. He has books on the old chemical works which cover the explosives during the war. I have just joined ‘Streetlife’ which covers our local area. I put up a comment about mining and got a very good response. It is surprising how people are interested about the local mining. On Tuesday one couple hired a car to come down from Newcastle to listen to the lecture and both enjoyed it. Another lady on ‘Streetlife’ sent me an email to say she was sorry she could not come on Tuesday, but could I send her information about the exhibition I am at, at Hardcastle Crags. I do not know who she is? Pam and Alan who wrote the book on Mining up the Holme Valley where both there. cheers roger Date: Fri, 10 Apr 2015 07:30:16 +0000 To: huddminelectures@outlook.com

Not this one, but in a way related. Read Holliday sunk a pit to supply his chemical works at Turnbridge, on Dalton Bank , I think from the description.

Grove Pit was put down by Read Holiday which later changed to British Dyes it is on and in Dalton Bank. It is by the bridge which used to cross the river. There is another shaft nearer Aspley and close to the river as well as Car Pit. There is also pits either side of the what is now the Cricket Pitch at Rawthorpe. We have yet to find Moldgreen Colliery.

Grove pit had shafts and adits.

Roger 10/4/15 9-36

Hi there,

I used to live on the top of Kilner Bank, and remembered a capped off shaft halfway up the banking from the river to Kilner bank road (below the row of bungalows) a bit of the concrete was broken away at the corner, and you could climb inside and look down the seemingly bottomless bricklined shaft. have you any idea what shaft this was? and also are there any plans to show the workings of this and the ones near the cricket pitch?

Thank you in advance!

Martin

It may be this, recorded from 1894 HEW 28 Apr: Kilner Bank, Read Holliday & Co sinking pit to Halifax Old Bed, 115 yards deep, another 15 to 20 to go. Boiler, powering pump, explodes. For any plans your best bet is to contact Roger Lynch. fixbylad@hotmail.com

Hi. In the region of Kilner Bank there is a pit either side of the Cricket Pitch and some adits in the old quarry. Below the bungalows there is another shaft near the River. There is a slight rise of the ground above the river and the shaft is on the flat above this. You remember a shaft part way up the bank from this. I have not looked for one there but it is very possible because further on there is ‘Grove Pit’ Holidays pit. This has a shaft and adits going into the bank. So there is possible unmarked adits and shafts anywhere in that region. roger

Thanks Roger

What was the length of a iron rail on which tubs ran in a Yorkshire coal mine in 1940 and was the Davy safety lamp used at that time?

The Davy lamp was used mainly for checking for gas by 1940 , and contined to be so used. A couple of times I had to work by the light of one when my lamp battery went out. Rails were about four yards long if I remember correctly. We used to transport them on 6 foot long trams and there was at least a yard overlapping at each end and chains had to be used to couple the trams together.

Re Jim Haywood’s letter. There are two books of interest which give conditions in the mine.

Victoria’s Children of the Dark by Alan Gallop BSN978 0 7524 0. Tells of the 1834 Husker Pit at Silkstone disaster.

Black Diamonds, The Rise and Fall of an English Dynesty by Catherine Bailey. ISBN 978-0-141-01923-9. Tells the story of the Fitzwilliams of Wentworth.

Plus all the small books on mining

roger lynch

.Re The Davy Lamp. The Davy lamp is usually classed as the lamp covered in gauze with no glass. The 1940 type lamps are more of the ‘Clanny’ Type with the glass circular window with the gauze above covered in a metal hood.

You’re right about the lamp of course, but most people refer to the safety lamp as a Davy Lamp. The point is, by the 1940s they were used primarily for testing for gas, rather than working by. Apart from the deputies etc who routinely used them for checking for gas, men who carried them got extra ‘lamp money’.

Thanks for the information (huddsludds) I’m researching for a novel circa 1940 set in South Yorkshire where some of the action takes place down a coal mine so much obliged

Hello,

I read the website with great interest.

There is reference to the possibility of an updated version of the research including coverage of mining in Huddersfield up to the 1920’s. Has that been undertaken?

I was also interested in the reference to research on the munitions.

I am tying my research to a historiography of the Irish in Batley (I am a Batley ex-pat) from an Irish background. My grandfather and uncles worked in the mines (Gomersall I think). My great Aunt died from poisoning a few weeks after starting work in a Leeds munitions factory. The rest of the family worked in the mills in Batley.

Thanks for your input and please keep up the great work.

Anthony Finn

Dear Anthony, thanks for your inquiry and interesting comments. I have done research on local mines up to the 1920s, but have not yet written it up. I’m afraid that it doesn’t cover Gomersal. There is an interesting account of ‘The Barnbow Lasses’ – Leeds munition workers, by Bob Lawrence in Leeds History Journal Issue 21. Is this the factory where your great aunt worked I wonder ?

Fascinated to find this excellent site. I’m trying to research two mines which I believe were on Northfield Lane Highburton. One at Busk farm I have managed to get mine abandonment plans for. The other simply named Northfield I have been unable to find anything. I wonder if you have come across the name in any of your research. Amazingly there are some 37 listed mine for the Kirkburton and Highburton area alone. !

Ian, i haven’t come across Northfield. If I do I will let you know. I am not surprised by the number of listed mines, the whole area is riddled with them.

Hi, I have picked up your email to the mines at Highburton. Can you email me on this so I can send you a plan. I have ‘Busk Pit’ two fields to the north of Busk House, plus there is another shaft and three adits. Between Busk and Northfield House is another adit. We are having trouble with Northfield Colliery, but think it is just North East of Northfield house. please contact roger at fixbylad@hotmail.com