The text below, originally published in a now long out of print booklet, was written to commemorate the centenary of Honley Socialist Club in 1992. Since then, new material, including a biography of one of the local Socialist pioneers, France Littlewood, has been gathered, and awaits incorporation into a revised account.

INTRODUCTION

Honley’s long tradition of Radical politics stems from the years around 1800, as handloom weavers, croppers and other artisans resisted the economic and social changes forced on them by industrialisation and an undemocratic political system that safeguarded the interests of the rising class of wealthy manufacturers. In these struggles, a dynamic popular culture of resistance was created with alternative ideals, values, aspirations and forms of organisation.

There are strong hints of republican “Jacobin” activity in the township during the period of the French revolution, when Corresponding Societies and the more militant United Englishmen certainly had a presence in Almondbury and Huddersfield. In 1812, although several Luddite attacks were carried out, no local croppers were prosecuted, but, in 1817, following the attempted Radical uprising, a number of Honley croppers and weavers were charged and one prominent leader, George Taylor, ‘the Honley huntsman’s son’, went on the run. Honley was one of the first townships after Almondbury to establish a radical Political Union for parliamentary reform in the 1830s, and there was support for the Republican politics of Richard Carlile. Struggles for the free press, for factory reform and against the New Poor Law all had local adherents, whose efforts culminated in the formation of a Chartist Northern Union in 1838.

This same year, Owenite Socialists rented their own meeting room in a cottage cellar at Berry Croft. Constituted as Class 19, they were a satellite of the No.6 Branch of the Association of All Classes of All Nations in Huddersfield which, in 1839, built a palatial Hall of Science in the town. The New Moral World, the Socialists’ journal, reported of Honley in 1844 ‘The cause of rationalism is progressing very well in this locality’ – but, in reality, the cause was past its zenith. The heirs of the Owenite tradition of philosophical materialism, the Secularists, still had some support up to 1861 and Joseph Jaggar of Honley Moor Bottom was a prominent figure in the movement in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

There no doubt remained individual enthusiasts for these ideas, as well as a folk memory, expressed in oral tradition and the reminisces of veteran campaigners, which kept alive the memory of popular struggle. This is reflected in the 1880s by a certain curiosity, if not nostalgia, for the early days of industrialisation, in the local press. A romance, ‘Beaumont’s Lad’, serialised in the Huddersfield Examiner in 1883, painted a picture of Honley earlier in the century, and described this alternative radical culture in terms which could apply to its Socialist Club successor:

There was in Honley many years ago and still is, a room which was known to the inhabitants as “Th’ Garrit” … a Cave of Abdullam, where gathered the originals of the district, whether cobblers, given then as now somewhat to freethinking in matters religious, or radicals, admirers of Robert Owen, who found the atmosphere of the National Schools too close and stuffy, or, on occassion, lads and lasses who wanted to dance and romp at Christmas time,but could not, as their betters, meet at each others’ houses for this not very dreadful purpose … The phrase “He goes to th’Garrit” thus became one of reproach in the mouths of good Church-going villagers who could not write their own names and did not want to, but one of a certain half mischievous and impish commendation in those of men who cared little for the opinions of “the stick-in-the-muds”, and a great deal for the education of their children and the “Rights of Man” … Weavers, farmers, dyers, all who were not quite agreed that the world as it ran was the best world that could be, met to devise improvements and point out where and what remedies might be made.

The revival of Socialism in the 1890’s set about the recreation of this culture of resistance, but in a different context. Now the vision of the future was based not on the rejection of industrialism, but on its subjugation to the needs of workers. Although the local growth of Socialism was part of a national, and even an international movement, the radical tradition of Honley undoubtedly contributed to its popular appeal, expressed in the vibrant life of the Socialist Club. [1]

WORKERS’ CONDITIONS IN HONLEY.

By 1891, the population of Honley township was 5,466 – less than it had been in 1851. This decline accompanied the demise of handloom weaving and the emigration of people from the villages and hamlets of the Holme Valley to the towns, or abroad. The population continued to fall to 5,138 in 1901 and even in 1915 the birth rate was described as “remarkably low for some years.” There were about 1,200 houses in the area, many of those in the centre of the village being old and sub-standard and relying on the wells for their water supply. [2]

Wool and worsted textiles were the main industry, and in 1889 trade in Honley was said to be very busy. Following a general strike of weavers in the Huddersfield area in 1883, a pay scale had been agreed with the employers – but this was often ignored. The introduction of Dobcross fast looms after that year gave employers the excuse to put weavers on a lower scale, or to supplant men by women who were paid on a lower scale anyway. Similarly, in finishing and spinning there was a trend towards replacing men by lads. One weaver told a meeting of the West Yorkshire Power Loom Weavers’ Association at Honley in 1889 that he was only receiving 14s. 3d for a piece which should have paid 20s. 2d. according to the 1883 scale. In 1895 it was said that Honley weavers did not average 18s a week at a time when 26s was considered a living wage. [3]

There was a strike at Deanhouse Mill in 1894 when half the looms were speeded up, and wages for the fast loom weavers reduced while the slow loom weavers were kept idle waiting for warps. At Eastwood Bros. of Thirstin Mill, there was a dispute the following year over a wage reduction and again in 1902. Weavers at Reins Mill also struck in 1902 over the scale. At Queen’s Square Mills, Josiah France’s weavers had grievances in 1898, 1902 (when they secured an advance) and in 1906. In this year, 100 pick per minute looms were being introduced and the Union came to a general agreement with the employers concerning a new scale at the end of 1907. Nevertheless, France’s weavers were still unhappy until in 1908 they won a rate of 6d. an hour. [4]

The General Union of Weavers and Textile Workers, as the Weavers Association had become, argued in 1912 that there was no overall wage increase since 1883 and that a 15% rise was needed to compensate for the increase in the cost of living – a claim strenuously denied by the employers. A 55 hour week was also sought since weavers were working 59 to 70 hours. [5]

In fact, real wages in the textile industry at this time are difficult to calculate, since workers in different departments working on different goods had widely varying rates. Also, the fluctuating state of trade affected real wages. In the 1890s, local textiles were slightly depressed, recovering up to 1907, followed by a slump in 1908, before reviving steadily up to the World War, which meant a boom for firms involved in military contracts.

Workers in Honley therefore did not suffer the extreme poverty or widespread employment experienced in some other areas. Their Socialism was not motivated by acute material distress. But their need to constantly defend working conditions made struggle on the trade union’s industrial front an important element in their concept of Socialism.

THE BIRTH OF HONLEY LABOUR CLUB 1891-1892.

In July 1891, the Colne Valley Labour Union (CVLU) was founded by a group of textile workers and craftsmen at Slaithwaite. Although the leaders of the Weavers’ Association were present and the main objective was to win representation for labour on the local or national governing bodies, some, like George Cotton of Marsden, were already Socialists. A Fabian Society existed in Huddersfield and a Social Democratic Club in Slaithwaite itself. The CVLU members immediately began extending their organisation throughout the Colne Valley constituency. [6]

In September it was decided to send a delegate to Honley to meet two Liberals, France Littlewood, owner of a cloth-finishing firm at Grove Mill and the Reverend Briggs, chairman of the rate-payers Association. At a meeting at Meltham the following month, Briggs made clear his opposition to the formation of a Labour Party, but contact with France Littlewood bore fruit. He undertook the organisation of a meeting at the Wesleyan Schoolroom on 28 November. [7]

G.W. Haigh, secretary of the CVLU, and George Garside, its president, were present although the main speaker, Alfred Settle of Salford, ‘missed his way’ and was late. Littlewood moved the resolution: ‘That the time is now opportune to form a branch of the Labour Union for this district.’ A number of membership cards were taken by Littlewood and Ben Orcherton, an active member of the weavers’ Association, to begin the enrollment of members. [8]

The following August, the CVLU agreed that members in Honley begin preparations for a large meeting on 10th December addressed by Tom Mann. From that meeting Honley Labour Club was born. On the frontspiece of the new membership book dated 31st December 1892, its first secretary, Walker Swallow, wrote a brief epigram:

‘May success crown its efforts and leave the world a little better than they found it.’

By the following April it already had 74 members. [9]

France Littlewood

Having played a prime role in the creation of the Club, France Littlewood was prominent in its subsequent activities, his stocky red-bearded figure was familiar at Socialist events throughout the area for twenty years. As well as being the first president of the Club, he was vice-president of the CVLU in 1892 and treasurer of its election fund (to which he contributed £5 of his own money) in 1893. He was the CVLU representative at the founding conference of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1893 and later sat on the ILP’s National Administrative Council as treasurer. When Honley Mutual Improvement Society, of which he was a member, held a mock election in 1893 the ‘Liberal candidate,’ Reverend Briggs, criticised the Labour Party for ignoring the existing machinery to achieve its demands. Representing the Socialists, Littlewood replied that they must create a new machine for their own use and ‘he would be prepared to support all measures which had for their object the alleviation of poverty and the amelioration of the condition of the masses of the people.’ He was also involved in more parochial issues as a member of Honley Local Board, such as a controversy over improving the water supply to the hamlet at Hall Ing. He was also involved with the Cooperative Society and his many interests opened him to charges of faddism on at least one occasion. His relations with his Socialist comrades was not always harmonious, as we shall see. [10]

TOM MANN AND TRADE UNIONISM 1892-1894.

CVLU’s outlook is reflected in the choice of its candidate to fight the 1895 election. Tom Mann, an engineer, was a former member of the marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF), a leading advocate of the eight hour day and one of the organisers of the London dockers’ strike of 1889. His politics were a blend of marxist economics and christian preaching. From 1891, he regularly toured the constituency, speaking at a Honley Labour Club meeting at Moorbottom Chapel in December 1892. The next year, he addressed a crowd of an estimated thousand people at an open air meeting in a field belonging to the Cooperative Society on Cooperation, Sham and Real. [11]

The emphasis of Mann, and hence of the CVLU during this campaign, was more on trade union organisation than Socialist propaganda. In 1893, he produced a pamphlet ‘Appeal to the Yorkshire Textile Workers’ of which the CVLU ordered 2,000 copies for distribution. Few mills were entirely unionised – some workers not bothering to join until they were faced with a dispute – and activists were in danger of being blacklisted. But trade union solidarity was not entirely absent. When Mytholmbridge weavers struck in 1890 against the reduction of payscales for fast loom weavers, £8. 15s. was collected for their support by workers at nearby Rock Mill. Rock Mill, Reins Mill, Thirstin Mill and Queen’s Square Mill were unionised by the early 1900s. [12]

An attempt was made to boost local unionism in 1893 by a meeting of members of the gasworkers’, dyers’, railway servants’ and weavers’ unions at Moorbottom Chapel. The Labour Club also contributed towards promoting trade unionism. A visiting speaker, Fred Hammil, at a meeting in the Coop field urged them to combine trade unionism and Socialism by fighting for ‘all the results of their labour’. J. Fletcher of Huddersfield Trades Council spoke in November on The History of Trade Unions and, in April 1894, Mrs Marland of the London based Womens’ Trade Union League spoke on Trade Unionism and Cooperation. Ben Orcherton, co-founder of the Labour Club, was Honley delegate to the Weavers’ Association meeting in Huddersfield in 1890. T. Winterbottom, mentioned chairing a WA meeting at Honley in 1895, may have been the Club member Tom Winterbottom, and William H. Sykes of Dyson Hill, also a Club member, was the weavers union dues collector in 1908. The Club was certainly not parochial in its trade union views, since in 1893 the members raised 8s. for the striking Hull dockers. [13]

In 1893, the Independent Labour Party was founded at Bradford and, after some hesitation, the CVLU affiliated, its constituent clubs like Honley contributing towards the capitation fee. Two shillings was recorded in March 1894. From that year Tom Mann was not only candidate for the Colne Valley, but also secretary of the ILP. He was anti-sectarian and called on all Socialists to work together, considering the aims of the ILP and the marxist SDF to be compatible. In the pamphlet ‘What the ILP is Driving At’ he outlined his views:

‘…the objective of the two organisations is identical. It is the socialisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange, to be controlled by a democratic state in the interests of the community and the complete emancipation of labour from the domination of capitalism and landlordism and social and economic equality between the sexes.’ [14]

SETBACKS 1895-1906

Tom Mann was made a honorary member of the Labour Club, and his election campaign was energetically supported. It was fought on the basis of the ILP programme – an 8 hour day, relief work for the unemployed, state pensions for all over 50, payment of MPs etc. He collected over 1200 votes, about 13% of the poll, coming third place. Although this was a respectable result for the first Labour candidate in a strong Liberal seat, it must have come as an anti-climax to many of Mann’s supporters.

In 1895, Honley Club membership stood at 118. By the following year it had fallen to 111, and there were 26 resignations. Only 79 members were entered in 1897 – little over the 1893 level. This was symptomatic of the trend in the ILP both locally and nationally, where overall membership fell by about a third. Activity still continued however, and in 1897 the leading Socialist, John Bruce Glasier, visited Honley. [15]

CVLU became increasingly concerned about the decline of the member branches, and in February 1898 the secretary was instructed to write to Honley asking for an explanation of their absence from executive meetings. Honley was still causing concern in May, and at the December executive meeting it was resolved; ‘That Honley, Netherton and Delph be written to asking for a statement of their position in connection with the Labour Union.’ That year there were 19 resignations from the Honley Club, leaving only 56 members in 1899, and 39 the following year. When on 3rd March a meeting was called at Honley to reorganise Honley, Netherton and Meltham, only Honley delegates turned up. It is not suprising that there was a feeling in the CVLU that ‘something should be done to place the movement on a better footing’. In June a new constitution was adopted and the name changed to the Colne Valley Labour League (CVLL). [16]

Arthur Curnock, of Bird-in-the-Hand, Honley, was on the new executive committee of the CVLL. The reorganisation did not lead to the immediate revival of the Honley Labour Club. Entries in the membership book ceased at the end of July 1900, and only resume in July 1906. Only about 15 members kept the embers of Socialism glowing, encouraged by a further visit from Glasier in 1903. [17]

As well as the election set-back, the close of the nineteenth century in a blaze of nationalism was not a very congenial climate for Socialists. In 1887 there was Victoria’s jubilee, followed by her death in 1901, and an upsurge of patriotism resulting from the Boer War. All these provided the loyalists of Honley as elsewhere with the excuse for jingoistic ceremonies. Even Tom Mann left the country, becoming a trade union organiser in Australia.

THE REVIVAL 1906-1907.

Mainly as a consequence of the legal assault on trade unions marked by the Taff Vale judgement (which made unions liable for losses incurred by an employer during a strike), the Labour Representation Committee was formed in 1900. Its purpose was to organise trade unions, cooperative and socialist bodies to return candidates which would look after their interests in parliament. Twenty-nine such MPs were elected in 1906 on a Labour ticket, but in some areas this had meant coming to an agreement with the Liberals. This ‘Lib-Lab pact’ continued in parliament with the Labour Party, as it was now known, being careful not to antagonise the Liberals.

The “Labour Party “at this time was therefore only the same as today’s Parliamentary Labour Party. In the country, it did not exist as a single organisation, but drew its support from a coalition of trade unions, co-operative and socialist bodies – particularly the ILP. This distinction between the Labour Party’s parliamentary liberalism and the aspirations of the grass-roots socialists was to be a source of conflict within the CVLL and consequently the ILP as a whole.

Socialism in the Colne Valley was promoted by the publication of the Worker in Huddersfield in 1905, to support labour candidates in local and parliamentary elections, as well as ‘to direct our fellow-citizens to the Rising Sun of Socialism.’ This it did admirably until 1922. Arthur Curnock took out shares in it in 1907, and Honley sent delegates to the shareholders’ meetings. A tea and garden party was held at the Club in 1912 to raise funds for the paper. [18]

CVLL was not ready to fight the 1906 election, but it participated in the wave of enthusiasm. Honley Club increased rapidly from 13 members in 1905 to 79 in July 1906, when entries resume in the membership book. By the following year there were 185.

CVLL’s choice of Victor Grayson as parliamentary candidate, despite his failure to secure the endorsement by the National Administrative Council of the ILP, set the valleys afire with Socialist fervour. The Coop Hall at Honley was packed in February 1907 when he spoke on Socialism and the Classes:

‘…the time is now here,’ he concluded,’ not when an election comes, not when the enthusiasm is in the air, but now, here, let us consecrate ourselves anew tonight to the cause of Socialism which is the cause of humanity.’

The evangelical tenor of his speeches was reinforced by support from socialist clergymen such as the Reverend W.B. Graham of Thongsbridge, who spoke alongside Victor in Honley Market Place in July. He explained that he supported a socialist candidate because socialists were the only party ‘making an effort to carry out the moral teachings of Jesus Christ.’ At this meeting, Victor made a pledge which he later came to fulfill. ‘I would rather be a street corner agitator than a Member of Parliament on false pretences.’ It was this sincerity, this clarity of purpose, his appeal to the higher things in life that endowed socialism with the quality of a religious crusade, winning him the deep affection of the thinking workers of Honley. Their votes, in Grayson’s estimation, were for ‘pure, revolutionary Socialism.’ [19]

Honley was ‘painted red’ to greet Victor on his victory tour of the constituency. The role of the village was acknowledged in the Worker: ‘Of all the recent stirring scenes in the Colne Valley, Honley has been the centre and stronghold’. [20]

NEW PREMISES AT NEW STREET

Honley Labour Club’s membership was now so large that a new home was needed. Formerly, they had met in a room near Honley Bridge where the council offices now stand. On 31st August 1907, a new club was opened at New Street in an old handloom weavers type house. As celebrations play an important part in the Socialist movement of this time, it is worth describing the opening of the club premises in some detail, as ceremonies typical of similar events or Mayday parades.

At 2.30 p.m. in the afternoon, the procession left the tram terminus at Honley Bridge, headed by about 40 Clarion cyclists, followed by Honley Brass Band and then 300 children wearing red rosettes and ribbons, and the girls with red sashes over their white frocks. The landau carrying Philip Snowden MP and his wife, Victor Grayson MP and Mrs France Littlewood led the rest of the demonstration, composed of Socialists from all over the Colne Valley. Proceedings were delayed a while as the Khyber Pass, the alley leading to New Street, was blocked by the throng.

At the door of the Club, Philip Snowden, a gaunt sickly figure but a poetically powerful speaker, recollected that he had been at Honley before when ‘the gathering, to put it mildly, was hardly compared to this.’ He commended the members for having a temperance rule since, ‘he deplored the introduction of drink into a club as he had seen no good come of it. He hoped that the Club would be the centre of educational work in political and social questions.’

Honley Labour Club, opening of new premises 1907. Philip Snowden is speaking and France Littlewood is to his right.

Victor also outlined what he thought the role of the Club should be:

‘You can make this club a matter of historic importance if you like. You can make it a place where men and women are developed to carry our religion into all parts. You can make it a home of fellowship based on nothing artificial but on a joint conviction of faith … The war which they as Socialists were carrying on was against the ghastly forms of social evils and disease.’

After a joke from France Littlewood about being unable to afford a gold key, having spent all the ‘brass’ on electing Victor, Snowden opened the door to a hearty singing of the Red Flag. Tea at 10d. a ticket was provided for about 1450 adults in the National School. Festivities continued into the evening, when another meeting was held, and again closed by a rendition of the Red Flag. This was to be the beginning of annual Socialist demonstrations in Honley which, along with Mayday, was a highpoint of the local Socialist calendar. [21]

CULTURE AND COMMUNITY

What was the impact of the Club, and what role did it fulfill in the village? Although Mrs Jaggar’s ‘History of Honley’ describes the members of the Club as “very enthusiastic in their cause” the reader is left with no indication of the Socialists’ influence. But, at its height in 1908, the Club had over 200 male members. Approximately, along with the female members and children, this must have totalled around 500 people. Therefore (although some lived over the township boundary) around ten percent of Honley’s population was regularly involved in the activities of the Club. In addition, there were those Socialists who were not members. Sympathisers also must have been numbered in hundreds, while meetings and events on occasions attracted thousands. The Club was consequently an integral part of the community. [22]

For members, the Club was the focus of their social, cultural and educational life. It was never merely the headquarters of a political party, for it provided all the shared experiences of ceremonies as well as shared beliefs and values, that bind people together in a community. The Club building played the same role as the meeting house of a religious community – a community whose religion was Socialism. It offered a protective togetherness to those who rejected the established ideas of capitalist society. Its strength lay in the ability to involve all sections of the working class community in a wide range of political and social activities.

Women

Only men are recorded in the surviving membership book of the Club, but in 1911 the Worker referred to 70 women members, or “women comrades” as they are referred to, in another report. What rights they had as voting members is not known, but these were probably restricted. Women’s activities were mainly in a separate sphere and they had their own secretary. Despite this, their role was vital, and the Club could not have been built without their fundraising efforts and organisational abilities. A sewing club was formed to make goods for bazaars for the election fund (1893) or the building fund (1911). Teas and socials with singing, dancing and recitations also raised money. One such event was held for the piano fund in 1907. As well as catering at such functions, women also had to provide meals for hundreds of people at the annual demonstration. This auxiliary role did not mean that women took no interest in political issues. Such questions as votes for women they could hardly ignore. [23]

It was not reported how many women were present to listen to Mrs Mitchell of Ashton who spoke to the Club in 1906 on women’s suffrage. It was male members who moved the vote of sympathy ‘for the women in the fight they were making for political freedom.’ In reply to a question at his Honley pre-election meeting Victor affirmed that ‘ If woman was made an outlaw she had a right to rebel’ and he acknowledged the contribution of women to the campaign during his victory speech. His statement that Socialists wanted equality of the sexes, ‘abolition of the sex ties’, was interpteted in the hostile press as advocation of free love! [24]

At the Honley Socialist demonstration the following year, France Littlewood made a point of referring to the number of women present, and congratulated women in general for the recent London suffrage demonstration. The speaker, W.C. Anderson, elaborated on this;

‘Socialism brought a message for women as well as men. Every Socialist question was a woman’s question, as well as a man’s.’

This theme was repeated by Victor in Honley in 1909. ‘They [women] are fighting not only for the vote … they are fighting for the freedom of the children, the freedom of the men, the freedom of their own class.’ [25]

Considering the strength of Victorian family values, it is hardly suprising this found a reflection amongst Socialists. One problem discussed by the CVLU, and put to the ILP conference in 1893, was the prevention of married women working in factories. Partly, this was to prevent them undercutting wages, but there was also a strong element of the belief that married women belonged in the home, not winning bread. This concept of the sexual division of labour was carried on in the role ascribed to the women in the Socialists Club. Morevoer it was sometimes to women as mothers that Socialism made its appeal. Mrs Bridges Adams, speaking at Honley on Social Parentage in 1909, said ‘no home could live to itself and for the sake of their own children, mothers should do everything possible to secure the well being of all children.’ [26]

Children

Children were involved in the life of the Club in a way which made them feel that Socialism could be fun. The Socialist Reverend F.R. Swan reported his visit to Honley in 1907, when he was called upon to entertain 120 boys and girls crushed into the upstairs billiard room of the Club in New Street. The Red Flag was sung with gusto and the Socialist Sunday School ten commandments recited several times in an effort to keep them quiet. Asked for an example of courage, one of the boys shouted ‘ A Socialist’ and a girl ‘A Suffragette’. [27]

The children traditionally led the Honley demonstration dressed in their best, with rosettes and sashes and bearing ‘bannerettes with suitable mottos’. At the bazaar for the building fund in 1910, a children’s day was held with speeches and recitations presided over by the childrem themselves. Declaring the bazaar open, Miss Nellie Jubb said:

‘Our object is a worthy one. It is to help to build a new club for our fathers and mothers and it is our duty as children to help in this business because when we grow up we shall be able to carry on the work they are doing now.’ [28]

Sports and Games

Both adults’ and childrens’ recreational activities were organised by Club members. In addition to running, skipping races for girls and sack races for boys were popular. Whist and billiards were played by the adults, either in matches against other Socialist Clubs like Netherton (1908), or Kirkheaton (1909), or in the form of whist drives and socials to raise funds. One of these was held on Boxing day 1913 for the newly formed Clarion Ramblers group which went on long treks over the moors. There were also some Clarion cyclists in Honley who combined spreading propaganda with recreation. Nine of these went for a run over the ‘Isle of Skye’ in 1908 and at the opening of Netherton Socialist Club in the following week, a best decorated cycle competition was held. There were 120 members of the Huddersfield Clarion Cycling Club in 1906. [29]

Music

As in church or chapel, no ceremony or social was complete without music and singing. Honley, or sometimes Meltham Mills, Brass Band provided the music at several Socialist demonstrations and on the Mayday march into Huddersfield. However at Honley Socialist Club’s New Year tea in 1909, the newly formed Milnsbridge Socialist Brass Band entertained, giving a rousing rendition of England Arise in front of the Liberal Club and then marching off to the Marseillaise. Honley Socialist Choir also made its first appearance conducted by W.A. Burhouse (also a noted soloist). As well as performing at Club functions, this sang at Huddersfield ILP rooms under France Littlewood (1912) and won the choir prize at Honley carnival (1914).

The Comrades’ Song of Hope was a popular number, as well as non-political pieces such as Awake Aeolian Lyre. Concerts were also provided by several Club members who were talented solo singers, violinists or pianists. Dancing often accompanied both outdoor events and Club socials. Socialists made sure that not only the devil, but also that the church and chapel did not have all the best tunes. [30]

Education

One of the main functions of the Club was education, both in the sense of propagating political ideas and also in the wider sense of ‘self-improvement’ and intellectual stimulation. From the revival of the Club in 1906, to the opening of the New Street premises in 1907, 80 lectures were held on many topics from ‘The Basis of Industry’, ‘Competition versus Monopoly’ and ‘Class Struggle’ to ‘France Littlewood on Dust’. A library was accumulated, and newspapers and Socialist journals subscribed to. Socialists also supported the Adult School movement which held classes in Honley. There is no evidence for the formal eduction of children until the founding of Honley Socialist Sunday School in 1918, but according to the Reverend Swann, they certainly knew the SSS precepts in 1907. The nearest SSS was held in Lockwood. [31]

Council Elections

The Socialists demonstrated their concern about the daily welfare of the community by involvement in local administration. France Littlewood secured a seat on the Urban District Council in 1893 with 54 votes. He had sat as a Liberal in 1891 and some probably voted for the man rather than his principles, since his fellow Socialist, Tom Winterbottom, only got 24 votes. Standing in 1896, Littlewood failed even to get this number and with the general decline of the Club, no election was contested until 1907 when Littlewood regained a seat. [32]

Classes on Local Government were begun in 1908 with a talk by the UDC clerk, followed by lectures on Rating and Assessments and The Housing Problem. In a by-election that year, a Socialist blacksmith, G.H. Barrowclough, won with 107 votes, despite the fact that his Ratepayers’ Association opponent had three cars at his disposal and the Socialists only one trap. Willie Boothroyd stood for a vacancy in 1909, and Littlewood provoked an angry response from G.T. Oldham when he claimed that Boothroyd had been sacked from Oldham’s dyeworks because of his candidature. Oldham replied that it was because Boothroyd’s type of work had been discontinued by the firm and Littlewood’s own record as an employer was not perfect. Socialist successes in the 1909 UDC election resulted in four Socialist councillors in Honley: East Ward, Barrowclough, 90 votes; Littlewood, 82; Central Ward, Thomas Temple Hirst, warehouseman, 233; Tom Carter, mechanic,222. They were joined the next year by John Whitehead, a warper, and in 1911, following Hirst’s resignation due to marriage, by Harry Lee, a weaver. With 5 out of 12 seats, Honley UDC had a higher proportion of Socialists than any other neighbouring UDC. [33]

THE SPLIT FROM THE ILP 1908-1910.

Despite the apparent harmony between Grayson and Philip Snowden at the opening of the Club in 1907, relations between the new MP and the Labour Party were already strained. Victor had already declined to sign the LP constitution and accept its discipline. Snowden had initially refused to speak at the Honley opening if Victor was present, on the basis of distorted press accounts of Victor inciting strikers in Belfast to fight back against troops. They needed no inciting to resist – he only asserted their right to do so.

In parliament, Victor was not impressed by the etiquette and ridiculous conventions. His patience wore thin as irrelevant subjects were discussed, while the question of the unemployed was ignored. In 1908, he embarked on a campaign of disruption to force a debate on unemployment, resulting in his suspension from the Commons. The LP refused to back him up, but the CVLL commended him on his stand. The 1908 ILP conference held in Huddersfield was dominated by the dispute over why Victor had not been endorsed by the NAC of the party in the first place. Underlying this was growing disillusionment over the readiness of ILP MPs like Snowden and Macdonald to tone down their Socialism in parliament.

The CVLL was one of the largest affiliates to the ILP and the Honley Club the largest within the CVLL, with 216 male members in 1908 and 15 delegates on the CVLL executive Committee. Visiting Honley in 1908, Jim Larkin, organiser of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, who had spoken in favour of Victor at the ILP conference, said it was an inspiration to be in the Colne Valley, ‘there was nothing of the sloppy Lib-Lab about them.’ To signify its dissatisfaction with the LP and all that entailed, the Council meeting of the CVLL in September 1908 decided to change the name to Colne Valley Socialist League (CVSL). Henceforth, Honley Labour Club becomes Honley Socialist Club. [34]

France Littlewood was not happy with these developments, and in 1909 refused the presidency of the CVSL, but was persuaded to take the office. He resigned in December, explaining by letter his position, ‘I cannot allow myself to be identified with a candidature which is not in accordance with the regulations of the ILP…’ as this statement by a prominent member of the CVSL was released to the press, it is not suprising that Victor’s vote dropped by 500, and he lost his seat in the election of January 1910. Attacked by the press and Labour leaders alike, it is more suprising that he held on to over 3,000 votes. [35]

In a letter to the Worker in 1909, Littlewood outlined some of the ideas which underlay his alliegance to the ILP. Dismissing the viability of insurrection, he described himself as a ‘Political Method revolutionist, with a small r…” He explained that the physical force ‘held and used by the exploiters of Labour’ could only be captured by the Workers ‘through legislative and administrative bodies,’ and used in their own interest. ‘The “Physical Force revolution” by “Political methods” is the way to “Socialism”.’ [36]

In 1910 the CVSL council decided not to send any delegate to the ILP conference, although a minority thought they should try to influence the ILP ‘to return to a better way of life.’ France Littlewood wrote to the Worker in April strongly condemning the views of those who wished to secede from the ILP. He accused the ‘clean Socialists’ of ‘virulent sectarianism’ and ridiculed their strategy: ‘Parliament is of no use, Socialism can only come by preaching, by shouting and making oneself a general nuisance’.

He acknowledged that many of his opponents were friends who had worked hard in building the organisation and winning elections, concluding with a side-swipe at Grayson and the Graysonites. ‘To the fond hero worshippers of the Colne Valley I have little to say. Theirs is a mental disorder which time and the hero will surely cure’. [37]

One of the targets of his attack, Tom Carter of Moorbottom, a fellow Club member and UDC councillor, replied the following week;

‘We claim that the ILP since its absorption by the Labour Party has gradually deteriorated as a fighting force … the capitalists of this country fear it less than they did the small force of Socialists who voted for our comrades Grayson and Hyndman … I can assure comrade Littlewood that, I at any rate, will not sanction or condone the betrayal of our own class by the capitalist parties as the Labour Party has done on the question of the budget and the licensing bill, even though this may entail action on the lines which our comrade Grayson took on the unemployed question.’

It is worth noting the Tom Carter considered that, as well as Grayson Hyndman, the marxist leader of the Social Democratic Federation, represented his views. Tom Carter was evidently speaking for more CVSL members than Littlewood since in a ballot in May, 481 voted for the League’s secession from the ILP, as opposed to 178 against and 72 blank ballot papers. [38]

SOCIALIST UNITY 1910-1911.

Far from being guilty of ‘virulent sectarianism’ as Littlewood claimed, most members wanted real unity between all genuine Socialist organisations. Councillor T.T. Hirst of Honley, speaking on the ILP platform at the Huddersfield Mayday demonstration in 1910, expressed this desire:

‘There was some sectional strife in regard to policy in their movement but, at the same time, the rank and file was growing. He as a Socialist did not look to leaders but was prepared to stand shoulder to shoulder with his comrades of the working class to obtain Socialism.’ [39]

CVSL’s half-yearly council was held at Honley Socialist Club that September, and a resolution from Honley calling for a ‘United Socialist Party’ was adopted. It was resolved to send it to the Clarion, the most popular Socialist paper. E.J.B. Allen of the CVSL executive, and a member of the Club, was entrusted with receiving suggestions on Socialist unity from other clubs and drafting a resolution for the Clarion. [40]

On 4th August 1911 an article by Victor appeared in the Clarion entitled, ‘The British Socialist Party – Who is ready ?’ As the LP had irrevocably drifted back into Liberalism, there was a need for a genuine Socialist party uniting the marxist SDP and the various other Socialist groups and ‘any organisation which is desirous of making Socialists’.

At the opening of Honley Socialists’ new club that year, this was fully endorsed by the secretary Arthur Curnock, who moved a resolution which received unanimous assent, ‘That this meeting heartily approves of the proposed formation of the Unified British Socialist Party as suggested in this week’s Clarion and desires that immediate steps be taken to bring about the institution of a real, national, Socialist organisation.’ Honley thus played a pioneering role in the Socialist Unity movement which culminated in the foundation of the BSP in October 1911, a party which accepted the inevitability of class struggle and which was committed to the creation of a Socialist society. [41]

NEW CLUB OPENING AT ENFIELD 1911.

Socialist Club at Enfield House, Jaggar Lane, Honley. 1911 (Thanks to Peter Marshall and Honley Civic Society for this illustration).

The controversy over secession from the ILP and the loss of Victor’s seat cost the Honley Club some members, falling from 201 in 1909 to 159 in 1910, although it was still in a thriving state. Negotiations for the purchase of Enfield House on Jaggar Lane were completed in November 1910 before the expiry of the lease on the New Street premises the following April. The property, formerly the residence of Lupton Littlewood, a woollen manufacturer, was bought for £640 raised by loans and subscriptions from 100 shareholders. It comprised two cottages and gardens covering 1089 square yards.

About £200 worth of voluntary labour was expended by members to convert it to Club purposes, under the direction of a garden committee and a decoration commitee. Two gardens, a greenhouse, a summer house and a conservatory were refurbished or built. Joiners and decorators made a billiard room in the basement, a ground floor smoke room, ladies sewing room, committee room and steward’s living room, bar and scullery. A reading room, a concert room, card room, box room and steward’s bedroom and bathroom were provided upstairs. Electricity lit the premises and hot water was provided by gas. Members could have a bath for 2d.

On 15th April the completion of the ‘flitting’ from the old Club was celebrated by a members tea and, a fortnight later, an ‘at home’ with singing and supper was held by the female members in aid of the sewing fund. Goods made by the women were intended for sale at the Christmas bazaar, when it was hoped that much of the debt for the new Club would be paid off. £400 had been provided by members and £200 raised by functions, leaving another £200 to be found. T.T. Hirst designed a fund level indicator in the shape of a monkey climbing a tree to reach the target total of £800.

There was now no doubt about who had the best Socialist Club in the district according to the Worker. It was also an admirable example of the cooperation between the contending outlooks. France Littlewood, now Club treasurer, donated some pictures which were framed by E.J.B. Allen, while ‘Socialist and Labour laid turves, repose side by side on the lawns and the members cannot tell their own, and don’t want to.’

The official opening of the Club on 5th August, despite a rainy start, was well attended, with the procession led by Milnsbridge Socialist Brass Band. Tea was provided at Moorbottom School for 600 adults and 160 children. In the evening, a meeting and gala was held in the field next to the Club with games such as throwing three balls for a penny at a cut-out of Lloyd George.

Socialist Unity was the theme of the inaugural meeting. Arthur Dawson, a Marxist from Huddersfield, stated, ‘It was time the working class banded together into one organisation. Not by social reform but by social revolution was the only way out…’ This theme was reiterated by Victor Grayson, ‘That Club was not an exfoliation, but it had grown up around their own personalities. He hoped they would make it a centre of revolutionary activity.’

France Littlewood was not present at the festivities. He sent his best wishes but was holidaying at the seaside. It seems strange that he should miss such an important event for the Club, and we may conclude that it was intended to disassociate himself from Victor and the brand of revolutionary Socialism expressed in the speeches.

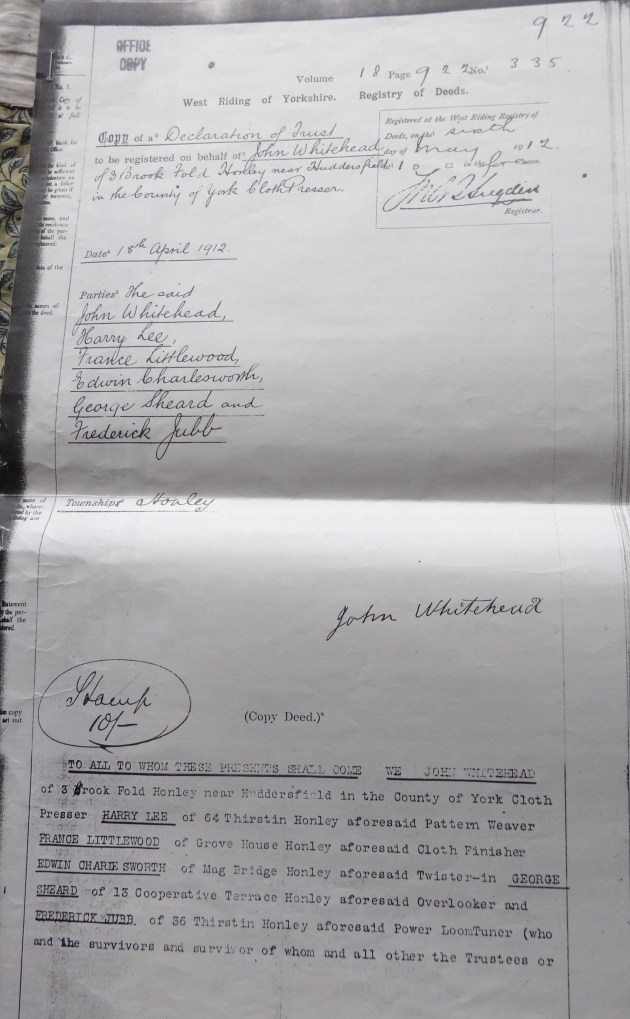

The enthusiasm generated by the new Club boosted membership to 192 by the end of 1911 and it stood at 176 the following year (not counting the women). In May 1912, the trust deed of the Club was registered naming as trustees France Littlewood; Harry Lee, pattern weaver of Thirstin Road; John Whitehead, clothpresser, Brooke Fold; Edwin Charlesworth, twister-in, Magbridge; George Sheard, overlooker, Coop Terrace and Fred Jubb, powerloom tuner, Thirstin. The Club was to remain temperance and was intended for ‘the propagation of the political and social views of the Labour and Socialist parties and for social purposes connected therewith…’

Clearly, all the strands of Labour and Socialist opinions held by members at that time were considered to have an equal place in the Club. The minority views of France Littlewood have already been described, as have those of the ‘Graysonites’ such as Tom Carter and Arthur Curnock. Another strand remains to be outlined – that of the revolutionary syndicalists represented by Ernest John Bartlett Allen. [42]

E.J.B. ALLEN AND SYNDICALISM 1909-1912

Originally a member of the marxist SDF, being the London Woodgreen branch delegate to conference in 1904, Allen joined a faction which broke away to form the Socialist Party of Great Britain. In 1906, having failed to commit the SPGB to support for industrial struggles, he joined the British Advocates of Industrial Unionism established by the Socialist Labour Party, editing the Industrial Unionist. Industrial Unionists, or syndicalists, believed that the only front of the class struggle which really counted was in industry. They aimed to organise industrial unions uniting all trades, launch a general strike and take over the mines, railways and other means of production to establish a Socialist cooperative commonwealth run by workers themselves.

In 1908, Allen and his supporters left the BAIU to form the Industrial League and in 1909, now in Huddersfield, he published a pamphlet on Revolutionary Unionism. In his capacity as national organiser of the Industrial League, he conducted a series of meetings at the Market Cross, chaired by George H. Greensmith of Paddock, an anarchist syndicalist. ‘Mr Allen gave an eloquent and forcible address’, reported the Worker, ‘He was logically plausible and such a full blooded extremist as to make a mere revolutionary Socialist feel that he was merely a weak kind of Whig. Mr Allen reminded one of Tom Mann somewhat, both by his vigour of speech and his appearance.’ In this year, Allen joined Honley Socialist Club, undoubtedly because he recognised fertile ground for his ideas. [43]

Industrial Unionism had been discussed at the Club the previous year when Fred Shaw of Lindley spoke on ‘The Necessity of a Revolution’ followed the next week by Greensmith on ‘How to realise the Socialist Commonwealth’. Jim Larkin from Belfast, the leading exponent of industrial unionism in practice, was the speaker at the annual Honley demonstration that year. [44]

Allen did not exclude the need for political action and was expelled from the Industrial League in 1910 for assisting Grayson’s election campaign. That year’ he was on the executive committee of the CVSL. In a letter to the Worker he explained his ability to combine different forms of action, but emphasised the basic need for syndicalism, ‘The ballot, the strike, sectional or general, “sabotage” and insurrection are all political methods when used against the government and we make a fetish of none but we use any or all … Industrial unity must precede all effective action of any kind.’ [45]

In May 1910, on his return from Australia, (where he had been influenced by reading Allen’s Revolutionary Unionism) Tom Mann joined the SDP, although syndicalism was still his main strategy. In July, he produced the first issue of the

Industrial Syndicalist which contained his manifesto ‘Prepare for Action’. He visited Honley on 1st August, as part of a tour arranged by the CVSL, and spoke at a meeting at the Market Place chaired by Allen. Recalling his first experiences in the Valley eighteen years before, he went on to summarise his view that there were two main things workers lacked, ‘One – Real solidarity. Two – The Class War feeling.’ and invited ‘the many local critics of Industrial Unionism’ to question him. [46]

Allen was the speaker, along with Victor, at the Honley demonstration that year. Referring to the CVSL split from the ILP he said there was need for a Socialist Party which would take into consideration the class struggle. He elaborated his ideas in an article in the Industrial Syndicalist in October entitled ‘Working Class Socialism’ which proclaimed:

‘Hurrah for the Class War! … The Industrial Unionist movement itself is a declaration of Social War – the war that shall cease only with our emancipation. For we too love peace, but not the peace of slavery.’

From September, Allen appeared in the Industrial Syndicalist list of speakers, his union being given as ‘gas workers’. In the 1911 Census he is recorded at 12, New Street with his wife Mathilda and five year old daughter Doris. His occupation is described as a borer for a bobbin turner. On 19 March of that year in the ‘large room’ of the club, the fortieth anniversary of the Paris Commune was commemorated with a lecture by Allen on the tragic history of this first brief attempt to establish a workers’ state. [47]

Class war could not be ignored in the years 1910-1912, which saw an unprecedented strike wave of miners, railway workers, dockers and others. Workers were shot in Liverpool and Llanelli, and gunboats stationed in the Mersey and Humber. Mann and others were arrested for sedition after publishing a leaflet calling on troops not to open fire on workers. On Mayday 1912, Allen spoke at a BSP meeting at Slaithwaite alongside Victor and Arthur Gardiner, a leading member of Huddersfield BSP, and in June, at the opening of Greenfield Socialist Club, he stood-in for Victor, who was suffering one of his now frequent illnesses. He declared that he wanted to see Greenfield made ‘the centre of political and social activities among the workers and that institute the headquarters of a union movement as was the Honley Club.’ Allen was obviously pleased at his success in Honley and indeed the presence of such a notable speaker, writer and thinker must have had an impact. His decision to resign from the Club and from the CVSL deprived syndicalism in the Colne Valley of its leading light. [48]

WAR AND SOCIALISM 1914-1916.

CVSL voted to affiliate to the BSP in 1912. This may have been at the root of Allen’s resignation from the CVSL in July, since a controversy erupted between the former leaders of the SDP, like Hyndmamn, and the pro-syndicalists in the BSP. Some branches, such as Huddersfield where Fred Shaw was active, made clear their support for syndicalism, but the collapse of the strike wave and of Mann’s Industrial Syndicalist Education League in 1913 contributed to the weakening of this tradition in British working class politics. The BSP also suffered, membership slumping from around 40,000 to less than 10,000. This trend is reflected in the Honley Socialist Club, which fell from 192 members in 1911 to 149 in 1913, when there were 15 resignations and 4 expulsions. In the CVSL, there was an element of dissatisfaction with the BSP, particularly due to the continued influence of the old SDP leadership and an attempt was made at the half yearly council meeting in October 1913 to disaffiliate. [49]

Edwin Charlesworth was the Club delegate to the CVSL executive, which in August resolved to reconsider the terms of its affiliation to the BSP, since they could not meet the financial commitments. By May 1914 they owed £9. 12s. 6d. in affiliation fees. That year they objected to the BSP executive about a circular interfering with their arrangements for a speaking tour by Victor, who was still the CVSL’s parliamentary candidate. [50]

In 1914, he spoke at Honley for the last time. He referred to his bankruptcy and attacks on his lifestyle, saying that ‘saviours of the people’ were crucified by more subtle methods than formerly. Two leading Huddersfield BSP members, Fred Shaw and Arthur Dawson, were also present. Tom Carter, chairing the meeting, commented:

‘the Labour movement was suffering from lack of suitable leaders and from too few Graysons and Larkins. It also suffered from lack of a guiding principle; and the principle it needed was the abolition of the wages system’

In a few months the movement was confronted by an even greater crisis, which not only spelt the end of Victor Grayson as a popular leader, but also the complete disarray of Socialist forces all over Europe. [51]

Although on the outbreak of the world war the Hyndmanite leadership of the BSP adopted a ‘social patriotic’ stand, regarding the conflict to be a defensive one against Prussian militarism and actively supporting recruitment, many branches, including Huddersfield and the CVSL, did not. Honley was no exception locally. In November, George Dyson of Honley Citizens’ Defence League visited the Club to issue An Appeal for recruits – Your King and Country need You! ‘Questions followed’, reported the Worker, ‘and they followed thick and fast in which it was clearly shown the Socialists’ view of militarism and warfare … Everyone was well pleased with the lecture and discussion and would be glad to hear Mr Dyson again, but on a more humane subject.’ Club members were more enthusiastic about a talk the following week by H.B. Flanders, an anarchist and anti-militarist on ‘The Power of the Workers of the World’. [52]

When conscription was introduced in 1916, several Honley men went to gaol rather than compromise their Socialism by supporting militarism and war between imperialist powers. Their motives were often mixed, with christian and humanist ethics reinforcing their political opposition. Objectors to military service had first to apply to a local tribunal and then, if exemption was refused, they had the right to be heard by an appeal tribunal. If they were still denied exemption and refused to withdraw their conscientious objections and report to their regiment they were liable to arrest and imprisonment in military or civilian gaols. [53]

Four un-named conscientious objectors (COs) who appeared before the Honley tribunal were interrogated about their beliefs, particularly how their consciences allowed them to be employed in jobs which contributed to the war effort. One weaver replied that he even objected to weaving khaki cloth and a yarn room assistant affirmed, ‘When it is a question of the military machine, if there were no other means of existence than by joining the army, I should be a pauper first.’ A BSP member who worked as a twister-in said his organisation had always been opposed to warfare and he called on the clerk to the tribunal, his former Sunday school teacher, to confirm that he had long held such beliefs. Only his trade union had saved him from the sack for not joining up already. The last applicant refused to answer such hypothetical questions but quoted the Socialist Sunday School’s ninth precept:

‘Do not think that he who loves his own country must hate and despise other nations, or wish for war, which is a remnant of barbarism.’

Concluding the hearing, the military representative on the tribunal described the COs as ‘a great evil, hindering recruiting tremendously’. In parliament, the ILP MP W.C. Anderson condemned this intervention, asking if such comments were not calculated to prejudice tribunals. [54]

Arthur Shaw of Honley, a quarry foreman, appearing at the Huddersfield appeal tribunal, also protested about Bradbury. His appeal being rejected, he repeated the SSS precept number nine and asserted that he had no intention of going to join the colours until the police came to fetch him. The yarn room assistant, 25 year old Francis Henry Sowerby, member of the Club, the ILP the No Conscription Fellowship and the Wesleyan Reform Sunday School, on losing his appeal turned to the public gallery and stated ‘I can assure everyone here that [I] will not give way even if it means death on principle.’ When arrested he threw the famous Burns quote at the magistrates, ‘Man’s inhumanity to man, makes countless thousands mourn’. Another SSS member, 28 year old weaver Beaumont Sykes, continued to refuse to report to the colours until the police came for him. A fine of 40s. was imposed to be deducted from his military pay. He ended up in Dartmoor gaol along with fellow Club member Arthur Hirst. At his tribunal, Hirst ‘denied the right of any man or set of men to say to him that he should take the life of any man.’ When Fred Swallow, 32, was told he was fined 40s. to be deducted, he retorted, ‘I don’t intend having any military pay’. [55]

Less outright opposition to the war was also expressed. Some claimed exemption on non-conscientious grounds such as family commitments, health or essential occupation. Some, like Honley’s first conscript, 20 year-old Norris Goldthorpe, a teazer at Rock Mill, simply failed to report on receiving his papers. When the PC turned up at his workplace to arrest him, he claimed he was under the impression that his employer had applied for his exemption. His father said he would have sought Norris’ exemption on the grounds he was needed on the farm if he had realised this was not the case. This may be the same Albert Goldthorpe who joined the Club the following year. In September 1916, Honley tribunal expressed concern that 48 local men exempted from military service were not fulfilling the condition that they had to drill with the local volunteers. Clearly, there were many men in Honley with little enthusiasm for the war, if not actively opposed to it. One of those was Horace Hampshire, who was 18 in 1916 and worked in the press shop at Tom Allen’s finishing works at Neiley. He deceived the Medical Officer at his call up examination by drinking ‘I won’t tell you what’ and smoking all the way to the examination, which pushed up his heart rate. His father, who was a staunch Socialist, also had a word with ‘the Labour man’ on the Tribunal and he was exempt on the grounds of ill health and the support he provided to his parents. He was also ordered to do home guard duty, but after attending drill at rock mill only twice he sneaked out and never went back. He claimed he was instead growing potatos for the war effort. [56]

In April 1916, the pro-war minority of the BSP split off to form the National Socialist Party. On the other hand, cooperation between anti-war Socialists was growing. CVSL passed a resolution reaffirming, ‘its belief in the principles of International Socialism and in our opinion the only war with which the workers are concerned is the Class War…’. However, it did not decide to promote an active campaign against the war, and did not even contest the elections of that year, simply issuing a manifesto practically postponing real struggle until after the war, ‘when something more than mere parliamentary elections may be required to remove the evils which the capitalist system has brought upon us…’. Anti-war speeches were made however, at a joint meeting of the CVSL and Huddersfield BSP and ILP branches at Slaithwaite in September and at Huddersfield in January 1917. [57]

Making a stand against war fever required principle and determination. Club membership fell from 128 in 1914 to 100 in 1915 and remained at that level throughout the war. Some financial difficulty may have been experienced, as Honley was late with its half-yearly contribution to the CVSL in 1915. A number of names appear in the membership book underlined and with no subs recorded for the duration of the war. Some like Arthur Hirst were conscientious objectors – others may have been conscripts who, reluctantly or not, reported to the colours.

THE FOUNDATION OF THE COLNE VALLEY LABOUR PARTY

Despite the opposition of the CVSL when the question was raised in 1914, the BSP affiliated to the Labour Party. In late 1916 however, the executive of the General Union of Textile Workers bypassed the CVSL to approach the Labour Party about forming a Colne Valley Divisional Labour Party (CVDLP). Annoyed at the ‘irregular manner’ of this move, the CVSL nevertheless acceded to the Labour Representation Committee’s request to call a conference in January 1917. Forty delegates from 11,000 members of Socialist Clubs, Coop Societies and Trades Unions agreed to set up a Divisional LP. Rules were drawn up and officers elected at a later meeting. W.C. Anderson MP spoke at the founding conference and in November visited Honley, addressing a meeting in the open air after the use of the Palladium Cinema was refused by the directors who wanted an assurance that the war would not be mentioned. [58]

What the attitude of the majority of Honley Club members to the LP at this time is not apparent. Ben Allen Noble, a former conscientious objector gaoled in Wormwood Scrubs, had gone as delegate to the inaugural conference, but the club continued to pay dues and sent delegates to the CVSL which was, in turn, affiliated to the CVDLP. John Schofield of Netherton, a former member of the Club who had joined in 1915 and left in 1917, now treasurer of the CVDLP, caused a controversy with a series of bitter letters in the Worker attacking Fred Shaw of the BSP. Shaw was the Yorkshire organiser of the Central Labour College, which sought to propagate marxist education, and in the winter of 1916/17 he ran a series of classes at Honley Club on astronomy, matter and energy, evolution and other scientific subjects. According to Schofield, Shaw was not qualified to speak on such topics, and he and other BSP members had attempted to take over the CVDLP. A number of letters appeared in defence of Shaw, and Schofield, meanwhile, resigned from the executive of the CVDLP. It was rumoured that he intended rejoining the Liberals. [59]

BETWEEN COMMUNISM AND LABOURISM 1917-1921

Many Socialists saw their vision of the future in the Russian Revolution of February 1917 rather than in the LP, bringing hope of an end to the war and the overthrow of capitalism. Even Labour leaders like Macdonald and Snowden were carried away by the enthusiasm and appeared at a conference in Leeds in June 1917, along with revolutionaries like Mann, Sylvia Pankhurst and Fred Shaw to support the Russian Revolution and set up a Workers and Soldiers’ Council. The Club’s secretary, Harry Lee, attended as delegate. [60]

John Whithead, the Club president, chairing a meeting of the CVDLP candidate Wilfred Whiteley at the Club ‘urged that the real enemies of the worker were not Germany and her allies but the capitalists of every country of the world.’ British intervention in Russia was discussed in September, and the following year the Club publicised Huddersfield Trades Council’s ‘Hands Off Russia’ demonstration of 20 July. [61]

This revolutionary fervour was even carried into the Socialist Sunday Schools. In May 1918, a SSS was opened at Honley Club with the superintendent of Huddersfield SSS leading the children in reciting the Socialists Ten Commandments and Wilf Whiteley bringing greetings from Lockwood and York SSSs, gave a talk on ‘plants, seeds and the functions of growth.’ The next year, Francis Sowerby organised the annual Yorkshire area SSS demonstration at Honley, ‘The sun shone and banners waved and the coloured dresses of the girls and women gave sparkle to the scene’. At the Market Place, Arthur Gardiner, a former conscientious objector and member of the No-Conscription Fellowship, spoke first:

‘With the seeds of social revolution now being sown in the far east the new world was being born. It was being brought into existence amid bloodshed and pain and it was for the workers who had a historic mission to fulfill, to join in completing the transformation to bring this country into line with others. He was not an advocate of violent or bloody revolution; the revolution would take place no matter how it was performed…’

Referring to the pupils of the SSS, Wilf Whiteley went on, ‘The last speaker had closed on a note of revolution. Revolution was here in front of them, the revolution in embryo.’ In allusion to his election defeat he said that these future voters would not reject a man because he opposed war. [62]

The CVSL was disbanded in 1918, and early the following year discussions were still continuing about the relationship of the Club to the Labour Party. A special meeting at Honley rejected a proposal to affiliate to the CVDLP and an explanation of its position from the CVSL veteran Sam Eastwood of Slaithwaite, now secretary of the CVDLP, met with no positive response. A fortnight later, Honley wrote to the BSP informing them that the Club was not affiliated to any national organisation since the disbanding of the CVSL. Many Honley members still retained their suspicion of the LP which had led them to split from the ILP in 1909. On the other hand they were not prepared to commit themselves to the BSP, preferring be free to cooperate with all Socialists. They in fact continued Socialist Unity in practice when the shock waves of the Bolshevik revolution were beginning to sharpen distinctions between left groups. [63]

In 1918 the BSP paper the Call was subscribed to, and the pro-war Justice belatedly cancelled. The following year, another paper which had supported the war, the Clarion was discontinued in favour of the militant Glasgow ILP’s Forward and the national ILP’s Socialist Review. BSP literature was advertised on the Club notice board. That this choice of reading matter also reflected opposition to the LP was evident when a recent member, Foster Lockwood, secretary of the Brockholes branch of the National Union of Railwaymen, stood in the council elections. It was moved by Lister Bintcliffe, the Club literature secretary, that the words ‘Labour Party’ be deleted from his manifesto and a commitment to oppose military training in schools included. The Club members had shown an interest in this subject by sending a delegate to a conference in Huddersfield on Militarism in Education in June 1918. [64]

The Club also discussed the plight of John Maclean, the leading Scottish Marxist, honoured with the post of Bolshevik consul and gaoled for his opposition to the war. Following his release, he was invited on an eight day speaking tour of the area in 1919 by the Club, including two meetings at Honley. Huddersfield BSP was given the first choice of two other nights, and he was offered to the ILP in Meltham, Slaithwaite, Milnsbridge and Holmfirth. ‘Workers, Rally Round this Great Fighter’ proclaimed the advert. Maclean talked to massive meetings at Honley Market Place on 26th May and 1st June on the theme that only revolution could avert another war. According to his report in the Call a ‘record’ meeting was held at Honley, and attempts were being made in the Colne Valley to establish ‘Workers’ Committees and independent educational classes in conjunction with the Central Labour College in Yorkshire’. Honley he described as the fighting centre of the Colne Valley division.’ Another prominent Scottish Marxist, Arthur Macmanus of the Socialist Labour Party, spoke at the annual meeting in August emphasising, ‘It was our duty to organise solidly, not with the purpose of running a strike, but for the purpose of revolution!’ [65]

The Club, along with CVLP and Huddersfield ILP, offered support to a Trades Council demonstration to protest at the breaking up of a BSP meeting at Greenfield by jingoists in 1919. Delegates were also sent to a joint meeting at the Huddersfield BSP rooms to discuss the formation of a ‘Workers Committee’. Friendly relations with the BSP are also apparent in 1920 when George Ebury (a BSP and later Communist Party organiser who assisted the founding of Huddersfield CP), came to speak at the Club and the BSP even selected Honley for its regional rally, asking the Club to do the catering. For its part the Club ordered a catalogue and a pair of ‘Best Sunday Boots, size 7D, to be purchased by Comrade Noble,’ from the BSP boot factory! [66]

Throughout 1919 and 1920, the BSP was in negotiations with other marxist organisations in an attempt to form a united Communist party, and in January 1921 the Club decided to receive a delegation from Huddersfield CP, ‘with the idea of forming a branch.’ Three months later, it was reported that a Communist group was being formed in Honley. There was still sympathy for the CP in 1923 when the Club began to subscribe to the ‘Communist Review’. [67]

INTO THE LABOUR PARTY 1922-1926

Ironically, the BSP had been affiliated to the LP, and the Communist Party sought affiliation, but the Club continued to refuse overtures from the CVDLP. In July 1919, letters from it were left to ‘lie on the table’, although in October the CVDLP was allowed use of a Club room once a month for 1s. 6d. At the same time as the Club was engaging BSP speakers however, they were writing to Labour leaders like Hodges, Macdonald and Bevin. The promotion of the Daily Herald was also supported. B.A. Noble attended a meeting in Huddersfield addressed by the editor George Lansbury in March 1922 and in May, a Herald development committee meeting was held in Honley and chaired by John Whitehead. The Worker ceased publication in this year. There was no niche for a predominantly local non-sectarian Socialists’ newspaper. [68]

In 1922 the Club also resolved to back LP candidates in the general election, although the choice for the Colne Valley was Victor Grayson’s old antagonist Philip Snowden. Following his victory an ‘at home’ was organised in the Primitive School rooms to welcome Mr and Mrs Snowden to Honley in January 1923. The following year, the committee finally decided to recommend affiliation to the CVDLP at the Club’s Annual General Meeting on the 27 January 1924 and ‘After a lengthy discussion it was moved that this Club affiliate but the number to affiliate be left with the committee.’ Later, the number was set at 50 and W.H. Sykes elected as delegate to the CVLP. [69]

Relations between the CVLP and the LP nationally were not always harmonious. In April, the CVLP delegate to conference was mandated to vote for a resolution calling on the name to be changed to Socialist Party, and in July a representative from the LP central office came to criticise the CVLP for bad organisation, particularly the low individual membership. In Honley this was almost nil, most being members by virtue of the Club’s affiliation. [70]

Honley also sent delegates to the ILP conference in September but, although it received circulars from the ILP regularly, it is not clear whether the Club was affiliated. Most members were still anti-sectarian, and a protest was sent to the CVDLP about a LP circular in 1925 prohibiting Communist affiliation. Huddersfield LP also ignored the directives, and a Communist was still on their executive committee in 1926. [71]

Concern was shown towards the industrial situation, and in 1925 Reggie Hartley was delegate to a LP conference on mine nationalisation and a dozen pamphlets ordered on ‘What the Coal Commission Proposes’. During the 1926 General Strike, the Club gave the railwaymen’s strike committee use of a room and following the strike’s collapse a ‘Committee for miners’ Wives and Children’ was organised in the village, with delegates being invited from religious bodies as well as trade unions. In October, a letter from Birdwell miners’ Distress Fund was displayed in the Coop draper’s window. Interest in international issues is reflected in the sending of two delegates to a conference in Huddersfield of International Class War Prisoners Aid, a body founded by the CP. Money was also donated to an appeal from the Youth delegation to Russia, and the letter put on the notice board. Fifty copies of a Daily Herald edition on Russia were ordered and Labour Party pamphlets on Vienna Under Socialist Rule. [72]

The Club also played an active part in the CVDLP. Francis Sowerby, who was also the Textile Union Honley branch delegate to the CVLP, was sent to the LP Conference in 1925 and 1926. Miss Nellie Buckley, also from Honley, was delegate to the LP’s womens’ conference. Honley was the venue for the CVLP annual rally in 1925 and the Club was given the dividend from goods bought at the Coop to provide refreshments. A tea was laid on in the Club followed by a whist drive and dance in the Coop Hall. [73]

Membership fluctuated throughout this period. Rising from a wartime level of 100 to 141 in 1919, coinciding with the crest of a revolutionary wave, numbers lapsed to 102 in 1921. A revival is apparent in 1923, with 136 members, and in 1924, the year of the first Labour government, a new peak of 155 was reached. In the year of the general strike, there were 21 resignations, leaving only 119 entries in 1927 when the first membership book closes. Veterans like Arthur Curnock, John Whithead and B.A. Noble continued to be actively involved, as well as former conscientious objectors like Fred Swallow, Francis Sowerby and Beaumont Sykes. With men such as these at the helm, the delayed affiliation to the LP is understandable. They had devoted much of their lives to fighting Labourism.

Receding hopes of revolution, and the failure of the CP to make a breakthrough in Britain, combined with the growth of the LP as a parliamentary force, persuaded many Socialists to throw in their lot with the latter. As an organisation which revolved around elections, there was a corresponding decline in Socialist zeal. The Socialist rank and file decreasingly felt that they were participating in the political birth of a new society. Politics became something people periodically voted someone else in to do for them. The TUC sabotage of the General Strike, and the isolation of the miners, demoralised those whose faith lay in the ability of workers to wage the class struggle. The Labour government’s anti-working class policies in 1929, and the defection of Colne Valley MP, Philip Snowden in 1931 led to further disillusionment. Activity moved from the realm of community life to that of a soulless bureaucratic machine, and the Socialist Clubs, built up painstakingly, with so much energy, time and money invested lovingly towards the advance of humanity, declined into mainly social clubs. A culture of resistance and of vision was transformed into a culture of deference and acceptance of capitalism.

REFERENCES AND NOTES.

1. Honley Rental 1838, West Yorkshire Archive Service, Kirklees, (Thanks to librarian Lesley Kipling for this reference); New Moral World 27th April 1844; Edward Royle Victorian Infidels p.296, 228, 249.; Huddersfield Weekly Examiner 24th March 1883.

2. Victoria County History of Yorkshire Abstracts of Census figures. Worker 3rd July 1915.

3. Yorkshire Factory Times (YFT) 19th July, 6th December 1889; 15th March 1895.

4. YFT 30th March, 6th April 1894; 3rd May 1895, 30th May, 20th June, 14th November 1902; 27th April 1906; 3rd January, 17th October 1908.

5. YFT 25th July 1912.

6. Colne Valley Labour Union (CVLU) Vol 1. Minutes 21st July. YFT 9th October, 4th December 1891.; David Clark Colne Valley: Radicalism to Socialism (Longmans 1981) for overview of CVLU.

7. CVLU 1 Minutes 15th September, 10th November, 17th November 1891.YFT 9th October 1891; Four Honley members appear in the 1892 January entry of the subs book, Ben Jaggar, James Sykes, Fred Jubb, B. Littlewood and W. Swallow.

8. YFT 4th December 1891.

9. CVLU minutes 27th August, 3rd December 1892,YFT 16th December 1892. Membership book 1892-1895 , in possession of Mr Lewis Walker secretary of Honley Socialist Club. YFT 21st April 1893.

10. CVLU 1 Minutes 7th May 1892, 18th March, 11th November, 9th December 1893; David Howell British Workers and the Independent Labour Party 188-1906 (Manchester 1983) p.309, p.320 and for an analysis of the development of the ILP nationally; Huddersfield Weekly Examiner 4th February, Littlewood got 36 votes to Briggs’ 46, the Tory only 5; 14th January 1893, letter from Littlewood, following week was a reply from “One of old gang” on the Local Board.

11. Tom Mann, Memoirs 1923; YFT 16th December 1892; CVLU 1 minutes 24th June, 1st July 1893; YFT 21st July 1893.

12. Clark, op.cit. Ch.4 passim; CVLU 1 minutes 27th August, 3rd December 1892; YFT 13th April 1894, a trade unionist at Honley Mill victimised; 2nd May 1890, Mytholmbridge Mill dispute.

13. YFT 2nd June; 11th August; 1st December; 1893; 6th April 1894; 25th April 1890; YFT 15th March 1895, The Club member may have been the warper Tom Winterbottom who lived at Grove Houses. An accident involving his son, who was kicked by a horse and died is reported YFT 4th July 1902.; YFT 24th October 1908, Sykes; YFT 21st April 1893.

14. CVLU 1 minutes 20th March 1894.

15. Honley Socialist Club membership book 1895-1927 (HSC mb); CVLU 1 Minutes 15th July 1897

16. CVLU minutes, 26th February, 20th May, 3rd December 1898; HSC mb; CVLU.1 minutes.

17. CVLU 1 minutes 23 Jun 1900; Colne Valley Labour League Vol 2, minutes 23 Jun 1900; 22 Aug 1903, Glasier; John Penny, who had replaced Mann after his resignation as ILP secretary in 1898 was also scheduled to speak. Ibid. 2 Oct 1904.CVLU/L membership book. 20 members for Honley district appear in 1900/01 but by 1904 this is reduced to 15

18. The Worker (W), appeared on 21 Jul 1905; W 1 Jun 1912.

19. W 16 Feb 1907; 6 Jul 1907, W 26 Jul 1907.

20. W 26 Jul 1907.

21. W 7 Sep 1907.

22. Mary Jaggar The History of Honley (Honley 1914) p.263.The Club is dealt with in less than 15 lines in which the opening of the New Street Club premises in 1907 is confused with the relocation at Enfield House in 1911; Non Club member Socialists include for example Mark Brooke, a conscientious objector in the war, who resigned in 1896 but whose brothers Hamlet and Havelock remained members.

23. W 1 Jan 1909; 5 May 1911; 28 Dec 1907.

24. W 15 Dec 1906,6 Jul 1907. Sylvia Pankhurst refers to the Womens’ Social and Political Union being ‘much in evidence’ in the election, but that once in parliament, Grayson ‘forgot all about the WSPU’. The Suffragette Movement. (Virago 1977) p.367.