In August this year I contemplated posting my account of the 1842 General Strike – or Plug Riot, as it has been disparagingly referred to. Unfortunately, same old story, other matters intervened and I have been unable to transcribe it from paper to the PC. As historical research has the habit of doing, I was looking for something else when I unearthed the article below which I had entirely forgotten that I had written. It appeared in the Huddersfield Examiner of 27 August 1992 to mark the 150th anniversary of the strike. Although this is only a barest summary of the event, and is in journalese, I have decided to post it to plug a gap in the website until such time as I can publish my full account. It has been OCRd so may need tidying up as I notice further typos.

IT was on a fine Friday afternoon in August, 1842, that a deputation of workmen entered the yard of Sykes and Fisher’s mill at Bankbottom, Marsden, demanding to see the owner. John Fisher angrily replied with the blunt instructions: “Get out.” A huge crowd then overran the mill. Some forced their way into the boiler house, knocking out the boiler plug, dousing the fires and releasing the steam. Others raised the “shuttle” (the sluice) to empty the mill dam and stop the waterwheels. Warning Fisher not to try to start his machinery, the crowd left.

The general strike, the so-called “plug plot,” had entered the Colne Valley. It had begun with proposed wage cuts at Bayley’s cotton factory at Stalybridge. The ranks of the locked-out workers swelled as they marched to neighbouring mills, workshops and collieries. Within a week, all of the manufacturing district from Stockport to Saddleworth was at a standstill.

“Turnouts” in one area moved on to the next in a growing wave. A meeting in Saddleworth then decided to spread the action over the Pennines. The strikers, estimated at 1,000 strong, who had marched from Saddleworth and stopped Fisher’s mill (on August 12), repeated the process at other works in Marsden, including Taylor’s foundry. Towards evening, they returned over Standedge. But this was only the beginning.

On Saturday morning a crowd of men, women and children, this time more than 5,000 strong poured over the moors. Any mills in Marsden which had resumed work were again stopped. By noon, the growing throng had reached Slaithwaite.

After refreshments provided by sympathetic, or intimidated, tradespeople, they continued down the valley, drawing plugs and opening shuttles on the way. So many mill darns were emptied that the level of the Colne rose noticeably.

Only at the mills of the Tory magistrates, Joseph Armitage, at Milnsbridge, and Joseph Starkey, at Longroyd Bridge, was any resistance shown. But even then the gates were forced and the machinery halted. By late afternoon, Huddersfield itself was in the grip of the strike.

Historians have focused on the willingness of some workers to defend the mills and be sworn in as special constables. But the Whig paper, the Leeds Mercury, noted at the time that the strikers “very generally amongst the working class met with much sympathy.” At a meeting at Back Green, local workers joined the Lancashire and Saddleworth “turnouts” in the demand for” a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay.” Some shouted “We’ll join you for the Charter,” and a resolution in support of the People’s Charter, with its programme for democratic political .system, was passed.

Sunday was quiet, marked only by the clattering into town of a troop of the 17th Lancers from Leeds to reinforce 400 special constables and the magistrates – stationed in the old George Hotel, looking on to the Market Place.

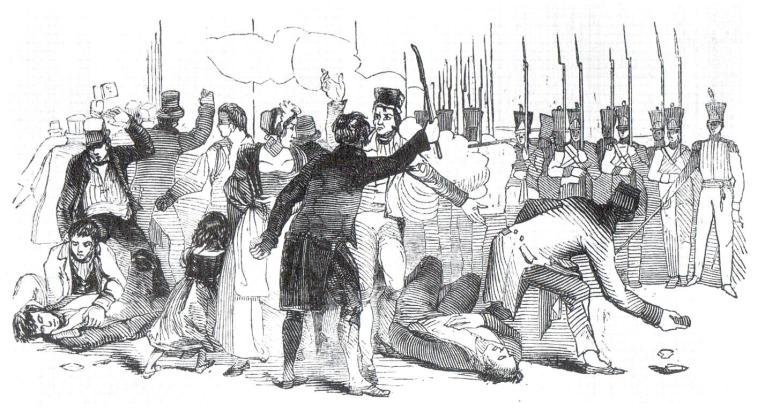

On Monday, August 15, columns of turnouts entered the head of the valley at Meltham and penetrated into the Holme Valley. Mill after mill was closed, along with Haigh’s colliery at Hall lng, Honley, and other pits. Joined by many local workers, the strikers streamed into Huddersfield again. Few mills had attempted to work that day. One was the mill of the magistrate., William Brook, who read the Riot Act, ordering the strikers to disperse. A charge by the Lancers temporarily scattered the crowd, wounding some. Arrests were made, including that of William Woodhead, a Lepton shoemaker. By now the Market Place, New Street and Westgate were packed with masses of people enraged by the military’s action. A delver from Linthwaite, William Holroyd, led an attempt to release the prisoners.

Again the Riot Act was read and the Lancers galloped into the crowd. Reporters for the Leeds Mercury and Leeds Intelligencer, who were in a bus near the Swan Inn, found themselves caught up in the attack. A fellow-passenger told the troops to “go to hell” and the reporters narrowly avoided blows from sabres and lances. “This sudden attack on the passengers cannot be too strongly condemned,” said the Mercury. One soldier was heard bragging that he had felled seven strikers. Among the most badly injured was an employee of Lords Mill, Honley, but locally, at least, there were no fatalities.

It was a different story in Preston and Halifax, where serious clashes between strikers and troops occurred. At Halifax, an attempt to ambush troops and release prisoners at Salterhebble led to the deaths of a soldier and two workers.

Huddersfield streets were cleared – but the strike continued to spread. Dewsbury and Batley were affected. Contingents of local strikers ranged up the valleys as far as Jackson Bridge and Holme, halting work on Bilberry reservoir. Others stopped Fenay Bridge mill, where Almondbury fancy weavers had been involved in a bitter long-running dispute with Norton and Wood. By Wednesday, the turnouts had reached Scissett and Clayton West, closing Norton’s Highbridge mills and Wood’s worsted factory at Spring Grove.

By Thursday, however, the impetus of the stoppage was lost. Exhaustion, lack of clear leadership, or aims, drove the strikers back to work. At least 34 people had been arrested in the Huddersfield area. Three of these were Lancashire men and three from Saddleworth. One was a woman accused of throwing stones at the soldiers. The rest were a local men in various occupations – weavers, shoemakers and labourers.

What had untied all these different workers in such a desperate venture? A correspondent to the Mercury described it as “a mysterious movement . . . one of the most strange and indefinite outbreaks that ever occurred in this country.” To the Whigs it was clearly a “Chartist insurrection” aimed at nothing less than a revolutionary seizure of power. The Chartists had unsuccesfully planned a general strike in 1839, but this time they were caught totally unawares. They saw it as a conspiracy by the Whig Anti-Corn Law League to lock-out workers and force the Tory Government to repeal the tariff on imported wheat. With cheaper bread, manufacturers could then lower wages. Meanwhile, the Tories blamed both Whigs and Chartists for fomenting unrest.

But there was no sinister plan behind the “Plug Plot” nor simply “copy-cat”rioting. The strike was a response to the appalling poverty of the early 1840s. It was a protest against the industrial system which enriched a few at the expense of the many Working people with no democratic rights had only one way to make their voice heard above the din of ever-advancing machinery. By silencing the mills .

The General Strike of 1842

by Mick Jenkins

(Lawrence and Wishart ,London 1980)

Mick Jenkins book is still the best one on the 1842 Strike – although mainly focussing on the Lancashire and Cheshire events.

(This critical review was written in 1980 for Labour Review, the theoretical journal of the WRP. Some of the topical (and embarrassingly Trotskyist) references have been ommitted and further bits added for clarification).

In this, still the most comprehensive account of the strike of 1842, Jenkins provides not only a readable description of the events and personalities , which should inspire and encourage all of us involved in today’s class struggle, but also an analysis which goes some of the way towards refuting the dominant academic historians’ view. He demonstrates that the strike was not simply a plot, (either of the Chartists or the Anti-corn Law League), as contemporaries of all parties claimed, nor a purely spontaneous outbreak (which the Chartists attempted ineffectually to manipulate) as many historians still claim. The General Strike of 1842 can only be considered as an integral part of the social and political development of the working class which was finding its identity against a background of rapid industrial change.

1837 saw the beginnings of an economic recession which plunged in 1839 into a full scale slump.By early 1842 there was massive unemployment, short-time working and wage cutting throughout all sectors of industry. In July of that year Staffordshire miners struck against reductions and the truck system , spreading their action throughout the coalfield by means which were to characterize the general strike of the following month. Large bodies of strikers marched in order from pit to ·pit and town to town persuading other workers to join them and where necessary closing down collieries by stopping the steam engines. Even more significantly mass meetings at Hanley and Burslem passed resolutions in support of ‘The Peoples Charter’. From the beginning the demand for “a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work” was indissolubly linked with the Chartist program for working class political rights.

Threatened wage reductions in the cotton manufactories of Stalybridge and Ashton-under-Lyne also led to a series of meetings in which local Chartists played a prominent part and in some cases successfully proposed resolutions for the Charter. On the 5th August the weavers of Bailey Bros. of Staleybridge struck against wage cuts and marched in procession the following day around the neighbouring mills which turned out in their support .On the 7 th, a Sunday mass meetings on Mottram Moor called for an extension of the strike not only to restore wages but also for the Charter to become the law of the land. That Monday the spreading of the strike began in earnest.

Processions of strikers marched into neighbouring towns , Hyde, ,’Stockport, Oldham ,Manchester. Some mills were forcibly closed and fights occurred with police and troops. By the 12th the strike had extended to Preston and Rochdale and by the beginning of the second week it was established in the West Hiding of Yorkshire. The authorities in some areas saw the movement as part of a general insurrection and troops opened fire on strikers in Preston, Blackburn and Halifax while in , Huddersfield they were charged by cavalry.

The organisation of the workers astounded the ruling class. The strike appeared so co-ordinated that it was suspected that ~ pigeon post relayed such information as troop movements from area to area. Strike committees were set up in some localities and dealt with matters such as dispensations for masters to finish work in danger of spoiling.

‘The Attorney General later stated ‘I have ever considered the existence of those committees as one of the most formidable evidences of the extent to which the ‘strike’ as it is called, pervaded all classes of operatives.’ He claimed moreover, that they had initially ‘…styled themselves committees of public safety” a title reminiscent of the French revolution.

Despite often thorough organisation and the political motivation of many workers, expressed at numerous meetings calling for the adoption of The Charter as an aim of the strike, the movement was crushed.

Having emphasised the role of conscious political leadership in the strike as the main thesis of the book the author reveals his own political weakness in his failure to explain the relationship of this leadership to the defeat .He in fact absolves it- completely. Contrasting this strike to 1926 (in which Mr Jenkins participated as a Communist Party member) he states: ‘The General Strike of 1842 was not defeated by the treachery of its leaders. On the contrary, there was unity and harmony between the workers and the strike leaders. They were defeated because of the superior strength of the ruling class.’ (p.24) However, the role of the leadership was a factor in the defeat of the strike, and particularly the part played by the Chartists who aspired to the leadership of the working classes.

In the second week of the strike a conference of delegates of different trades involved in the strike met at Manchester and declared themselves for the Charter and a further extension of the ‘cessation from labour’. The Home Office considered that ‘these delegates are the directing body; they form the link between the trades unions and the Chartists.’ However on the arrest of several delegates including the chairman, a Chartist and ‘socialist of long standing’, the conference issued a concluding address expressing exceeding regrets at the ‘…occurrence of the late civil commotion, of which we had not the slightest anticipation.’ and describing their earlier resolution for a strike ” for the Charter as ‘impractical’. They announced the intention to recommence the national strike for the Charter when their organisation was sufficient; ‘we shall do so legally and constitutionally and we fear not but the result will crown our cause with victory.’

The National Charter Association executive, at a conference previously arranged to mark the anniversary of the Peterloo massacre on the 16th August, published a stirring proclamation committing themselves to support of the strike and its peaceful extension. It concluded with an inspiring but not very concrete exhortation. ‘Strengthen our hands at this crisis. Support your leaders. Rally round our sacred cause, and leave the decision to the God of justice and of Battle.’ The conference also counseled workers against the destruction of life and property ‘Let all your acts be strictly legal and constitutional, and ere long your enemies will discover that labour is in truth the source of wealth, and should be the only source of power.’ This hardly supports Jenkins claim that “‘The strike of 1842 was originally the project of a minority of Chartist leaders and opposed by the rest. lts objective was the most ambitious possible – state power – even though it had built into it subsidiary economic demands.’ (p.250) He admits himself , in contradiction to his earlier praise of the leaders that the strike’s ‘… architects could be accused of making totally inadequate preparations for sustaining an underground leadership for the strike once a direct challenge had been issued to the government.’ Although he refers to the deep divisions within the Chartist body, particularly in relation to the abortive plan for a ‘Sacred month’ in 1839, he does not deal with the basic problem. What was the role of the Chartist movement as a whole and in all its conflicting tendencies in the strike wave of that year?

Only by attempting to answer this can we begin to understand the nature of the 1842 strike, Chartism and the working class in this phase of its’ development. The key can be found in the attitude of ~The Northern Star, the most widely read and influential of the Chartist newspapers especially in the counties most affected by the strike. As a weekly, it did not come of the press until Saturday the 13th when the strike was escalating most rapidly with the marches of the Lancashire workers into the West Riding. Its editorial of that day did its utmost to dampen support for these strikers already on the roads by denouncing the wage reductions as a plot of the Anti-corn law employers to shut down the mills to pressurise the government. More ridiculously, The Star asserted that the masters used this tactic ‘to prove that GENERAL DISTRESS exists’.~ To workers who were suffering actual economic distres- and who traditionally were accustomed to bringing this to the attention of government themselves this must have appeared to be an unconvincing claim. The masters intention, asserted the Star was, ‘…directed to the end of raising CAPITAL upon the ruins of LABOUR !’

Having made this condemnation of the strike the Star held back from an equally strong condemnation of the strikers themselves: ‘We offer no opinion as to the prudence or desirability of the TURN-OUT. that is a matter to be determined upon by the people themselves …’

The Star,as the voice of the northern Chartists had totally disassociated the organisation from not only leadership but also participation in the strike movement. It also warned members involved in an individual capacity “All attempts therefore to mix Chartism and the Chartists up with the STRIKE and the proceedings consequent on it are either insanely foolish or desperately wicked. ”’This must have come as a great blow to those working class Chartists busy agitating amongst the strikers for the adoption of the Charter.

Some were not daunted by these insinuations and events in Huddersfield reveal divisions which were more widespread than a reading of Jenkins book would have us believe. On Monday the 15th Lancashire strikers and those who had joined en route arrived in the town. At an open air meeting speakers stated their aims to be economic – a restoration of former wage levels – and disagreed with the.demands of some of the Huddersfield strikers of ‘The Charter or nothing’. Huddersfield Chartists claimed it was useless to go for better wages as long as labour was unprotected and a resolution calling for the adoption of the Charter was proposed and passed. Such meetings and debates accompanied the whole progress of the strike with the economic aim predominating in some areas.

The Tory Halifax Guardian which described the strike as a ‘Chartist insurrection’ claimed that the most willing strikers in Huddersfield were Chartists but that the leaders ‘were rather shy of exhibiting themselves during the commotions …’. This cannot be dismissed as a slur as the Huddersfield Chartists ,meeting to elect a delegate to the Manchester conference, issued a statement condemning both the use of the military against the strikers the previous day and the riots and disturbances which had led to the clash. At the end of the strike the local Council of the Charter Association sent a statement to the Star disclaiming any role in the Huddersfield riots as an organisation ‘… whatever may have been the conduct of a few individuals bearing the name.’ It also professed sympathy for those arrested but condemned ‘every effort to connect us or the Association of which we are officers with either the acts themselves or their consequences.’

Despite the involvement of working class Chartists in the strike therefore the Huddersfield Association adhered to the Star’s line of non-intervention. This would be justifiable if it only applied to acts of violence which might lay the Association open to legal action. But the constant appeals by the Star and its supporters to ‘Keep Chartism distinct from “risings” and “riotings”’ was orchestrated with both Whig and Tory outcries against the outrages of the strikers and by persistently dubbing the strike as an Anti-corn law plot it denied, along with those parties that the strike was a legitimate response to genuine grievances.

On the 27th the Star greeted the collapse of the strike with optimism. It smugly congratulated the Manchester trade delegates for having the courage to accept the futility of the strike and claimed that events had demonstrated to the trade societies the necessity for the Ch arter and legislative power to protect labour. More revealingly and in complete contrast to its attitude during the strike it claimed that the ‘honest of the middle classes’ had been convinced of the need for Chartist leadership in the working class by the lack of disturbance and anarchy in those areas where the ‘strike received a Chartist character’. After condemning working class Chartists wholesale for their participation in the strike, having left them out on a limb and undermined their support, the Star was attempting to gain credit from their efforts.

This crucial factor is not mentioned by Jenkins who portrays only the positive aspect of the strike; ‘The turn-out s of 1842 were undefeated in spirit; they had asserted their independence as a class and had demonstrated their class solidarity. They had exposed the vicious and brutal character of the capitalist state…They had experienced a new form of class action: the blending (sic) of the mass trade union movement with Chartism. They had seen what could be done with mass picketing. They had experienced certain elements in the exercise of working-class power, such as the issue of work permits by strike committees. they had seen trades conferences in action and becoming authoritative centres of local leadership.”(p.24) These successes, which appear here as a eulogy of pragmatism, obscure one vital development. Chartism as the authoritative leadership of the working class received a blow from which it never recovered.

Amongst the hundreds of arrests during and after the strike were many Chartists who had been involved enthusiastically and others who had just remained equivocal but this was not the main setback. The movement suffered from a wave of political disillusionment amongst its working class supporters due to its wavering during the strike. In the Star of July 29th the following year the Huddersfield district of the Association expressed hope that ‘The lull caused by the strike-plot will soon again be succeeded by the healthy breeze of Legal Agitation… in the worst of times there are a gallant little few who cannot be forced to abandon the cause…’ The role of the National Association in the strike, the consequent ‘lull’ and the diversionary schemes such as land allotments and emigration which the Star’ encouraged from 1843 onwards reflect the fundamental lack of organizational and theoretical clarity which characterised Chartism.

The root of this problem is revealed in Engel’s appraisal of the difference between Chartist democracy and all previous bourgeois democracy. ‘Chartism is of an essentially social nature, a class movement.’ Although this was realised by many of the Chartist 1eaders themselves they were unable to relate their political demands to the living reality of the class struggle. For them the Charter had to establish political rights as a precondition of social change and it had to do it through the existing political channel s backed by the pressure of mass education and organisation for Chartism.

Chartist trade unionists, on the other hand , could not divorce politics from the daily struggle in which they were engaged. They directly responded to the practical process of class struggle; the Charter was less an ideal and more a ‘knife and fork question’, a bread and butter question. This is why when the capitalists announced wage reductions the working class Chartists took the lead in the strike movement, attempting to politicize it by establishing the Charter amongst the worker’s demands, without stopping to consider if the Anti-corn law League was pulling the strings. Jenkin’s book does not really highlight this paradox – Chartism did provide the leadership of the strike. But it was also Chartism which did much to defuse the strikes

The Chartist leaders seemed unaware that the capitalists of the League were as much victims of the economic crisis as the working class and that the response to the threat to their economic interests was a reflex not a conspiracy. John Bright, a prominent Leaguer, in an address to Rochdale workers stated the immutable law of capitalism ‘…trade must yield a profit, or it will not long be carried on; and an advance in wages now would destroy profit…’ The workers were face to face with the enemy in this fundamental conflict of class interests -but the Chartists as a body were unprepared to lend their political leadership to a social struggle, the nature of which they did not understand.

It was the historical conditions of the birth of ‘the first workingmen’s party’ as Engels called Chartism, which placed limitations on it that it could not transcend. The 1842 general strike, as the most acute expression of class struggle under early industrial capitalism, epitomises all the contradictions of the political leadership of the working class in this period. These struggles are dominated by one fundamental historical process- the rapid progress of the capitalist mode of production. Integral to this was the growth of the working class, not only as part of the social forces of production but as an increasingly conscious agent of historical change. This consciousness did not grow mechanically and spontaneously out of class struggle as Jenkins book implies. The struggle against capitalist industrialism, landed capital and the relics of feudalism was expressed through all sorts of pre-existing ideologies. Chartism, although the political champion of the working class, was thoroughly pervaded by these elements.

Jenkins concludes with the assessment that; ‘the general strike of 1842 represented the climax of an already high level of class consciousness’ which asserted itself and ‘threatened a revolutionary situation …’ .(p.257) By ‘class consciousness’ he means primarily unity and organisation, the ultimate in trade union solidarity. ‘The test of working class conceptions of themselves as a class with a historical mission, is the degree to which the strike threw up and sustained organs for the specific purpose of a wider class organisation and the exercise of class power. The most important feature of this development was the creation of local strike committees …’ (p.181 our emphasis). Again he compares this to the 1926 strike when there ‘was the brief reconstitution of class unity which the Left managed to embody in councils of action and strike committees.’ (p.250)

Jenkins follows the teleological Marxist view of the working class. That is, he sees it as developing towards an ideal type of the proletariat as a class which is preordained to be the agent of historical transformation of capitalism to socialism. The weakness of this approach is that emphasis is put on the ways in which the working class and its leadership in earlier phases of development either deviated from, or failed to measure up to, its ‘historic tasks’. Luddism has sometimes suffered from this approach. We gain more of an insight into working class movements if we judge them in relationship to the conditions they were born under. Instead of seeing Chartism as a prelude to an opera which has not yet been performed (1), we understand it better as an opera in its own right, but at a level before the genre had been fully formed.

The Chartist leaders had no concept or desire to seize power in 1842 on the back of the strike wave. Even those Chartists who were involved at a grass roots level had not anticipated the spontaneous wave of enthusiasm for the strike. The 1842 strike was not a failed dress rehearsal for 1926. The Chartists, while being an essentially working class organization, were not an embryonic form of the Bolshevik party. Despite the conscious input from local Chartist leaders who did have some idea of their political objective, the most striking feature of the 1842 strike is its spontaneous nature and the enthusiasm with which it was spread. It did have, as Engels noted, the character of a popular rising, with strikers even taking on the state forces at times. Jenkin’s book vividly and sympathetically portrays the spontaneity of the movement as a creative act of resistance by the workers themselves. For this alone we forgive him any flaws the book may contain.

1. A reference to Trotsky’s observation ‘…in the whole general movement and in its theoretic observations there is much that is immature, incomplete …one may say that the Chartist movement is like a prelude which gives in an undeveloped form the music of the whole opera. In this sense the British proletariat may and must see in Chartism not only its past, but also its future’.